NB: The various texts have been reproduced as written in their respective years of publication. The word “Indian” is used incorrectly in identifying Indigenous peoples of North America.

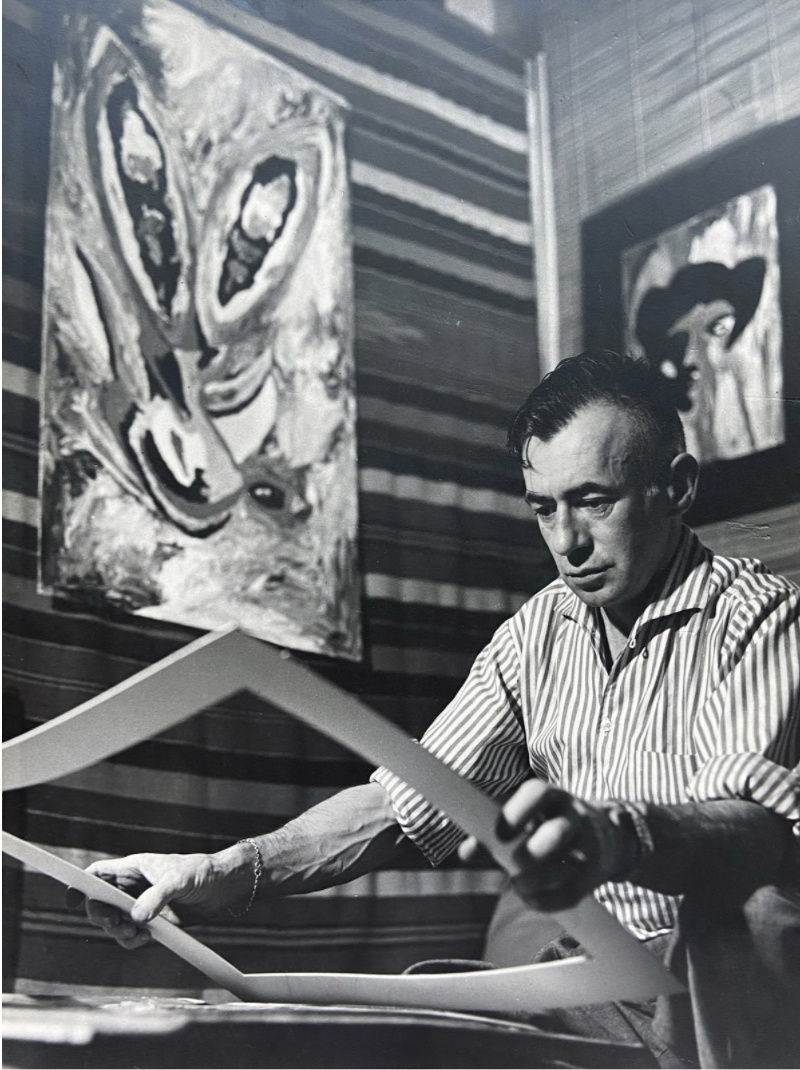

There is scant information on Sohaney, born Jack Douglas Howard Schoney Wilkinson. In the April 1957 Imperial Oil Review — for which our Lot 23, Untitled (Opposing Rooster / Fighting Cocks), was reproduced as a spread on the front and back covers — the biographical note on the artist reads,

A landscapist by profession, an artist by inclination and part Sioux Indian by ancestry — that’s the story of cover artist Jack Douglas Wilkinson, known as Johnny Canoe or Sohaney to his Indian friends. He signs Sohaney to his paintings because he feels the Indian influence is the strongest in his work.

Sohaney has been painting since he was an 11-year-old scampering around his mother's fruit farm at Penticton, B.C. His only formal studies in art were at the Slade School in London, England, where he attended night school for a short time during his wartime service with the Royal Canadian Navy. After the war he took a degree in agriculture at the University of British Columbia.

In his work he uses bright and primitive colors because, he says, like all Indian artists, he sees nothing gruesome. "All the universe is related," Sohaney explains, "and I try to express my ideas simply and directly, often through the symbolism of animals I know and can observe. However, there's no symbolism to the birds on the cover."

His Indian blood and sympathies Sohaney gets from his mother's side of the family. His grandmother Tsah-hilo, meaning Blue Sky, was a sister of Sitting Bull, an historic chief of the Sioux Indians. Sohaney has [been?] hanging in his Vancouver 10th Avenue studio Sitting Bull's marriage blanket [...].

His deep interest in Indian affairs prompted him in 1950 to establish Indian Times, a non-political, non-sectarian monthly magazine [1].

The publication, Indian Time, began in November 1950, while Sohaney was a student in agriculture at the University of British Columbia. He outlined his aims of the publication in the very first issue,

It is the policy of this publication to promote the interest and general welfare of the Indian nations. It will remain free from religious and political creeds. It will work for education; and health services, keeping in the mind the tradition of our fore-fathers. Only by full coordination of all groups can the Indian standard of living be lifted to surrounding levels [2].

The publication also aimed to see the “[r]evival of national crafts, folklore, music and dances [...]” [3]. As well as to facilitate the “[p]reservation of native culture and arts, linked with modern education and practical facilities is holy for Indian survival” [4].

Indian Time reproduced the art of Indigenous peoples alongside authoritative accounts of the social issues that the Native population faced and, above all, advocated for the self determination of Native peoples.

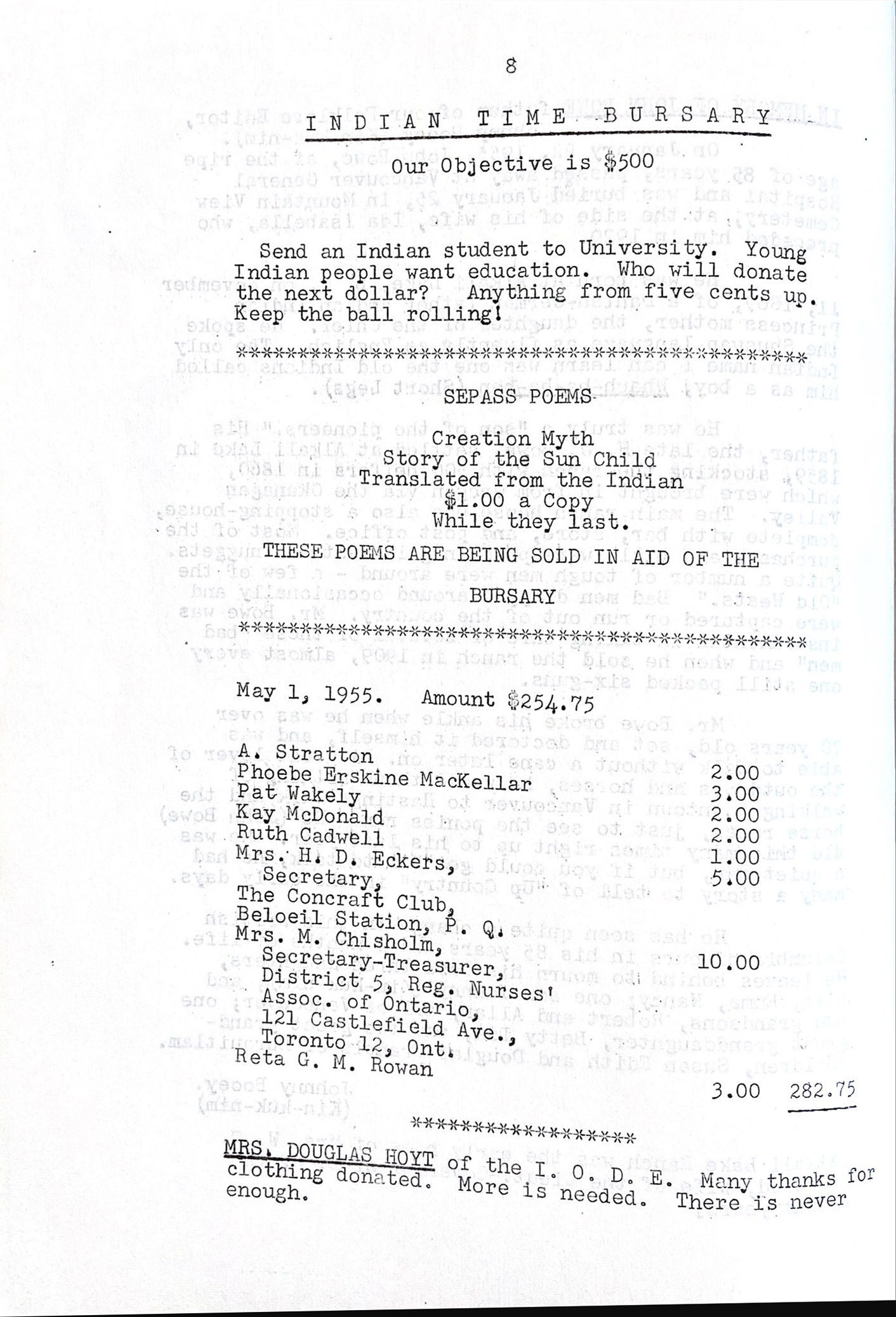

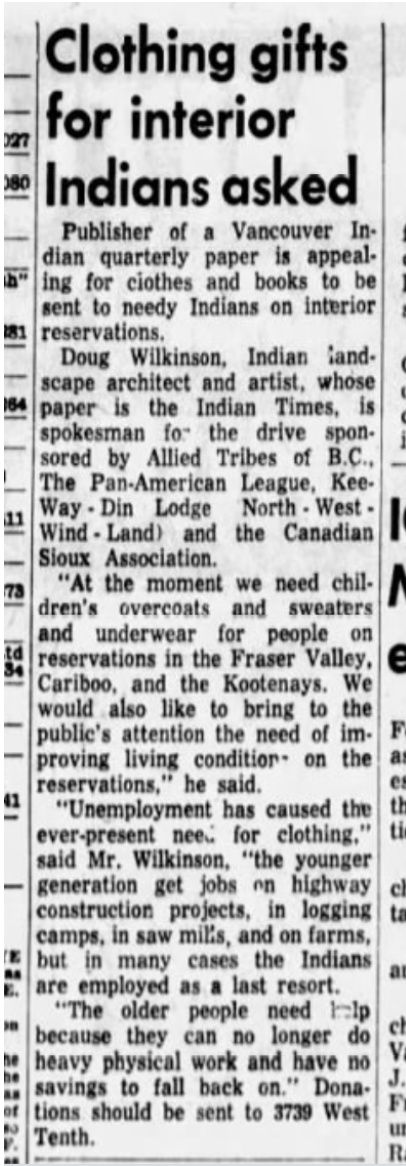

On the typeset cover page of each publication, the periodical touted itself “THE SMALLEST INDIAN PAPER WITH THE BIGGEST PUNCH.” Each issue was introduced with an editorial by Sohaney. Through Indian Time Sohaney appealed to his readership to raise funds for a bursary that would aid in sending a First Nations student to university and consistently urged subscribers to donate clothing and books to First Nations communities.

Eloise Street, editor of the magazine, said in a 1952 article, “You’d be surprised at the people who subscribe to Indian Time [...] folk[s] [...] who know that their [Indigenous peoples] problem is a problem made by the whites” [5].

|

|

|||||||||

| This particular example of the “Indian Time Bursary” is from Vol. 2, No. 13, 1957 [?]. The note at the bottom, addressed to Mrs. Douglas Hoyt, I.O.D.E. reads, “Many thanks for the clothing donated. More is needed. There is never enough.” | “Clothing gifts for Interior Indians asked”, The Province (Vancouver), 23 Jan 1957, p. 39 |

In his editorial from the September-December 1953 edition, Sohaney echoed the sentiments of the Imperial Oil Review biographical note, writing, “Indian Time has never been influenced by religious, political or financial pressures. It is an All-Indian paper for all Indians regardless of what, where or whom they are” [6]. Although Sohaney rejected the idea of political motivations in his publication, he remained an outspoken advocate for what he believed were grave injustices. He submitted several letters to Vancouver newspapers on a range of social and political issues, not limited to those facing Indigenous groups.

Forward thinking, in a letter to the editor of The Vancouver Sun on November 21, 1951, Sohaney criticized the Vancouver Art Gallery for their lack of handicap accessibility. “To erect such a modern and efficient building without a handrail on the steps shows a lack of foresight and human sympathy” [7].

It is difficult to explain Sohaney’s obscurity. Early critical reception of the artist lauded him as a promising, up-and-coming artist.

A 1951 publication of Smoke Signals heralded Sohaney as “... an artist rapidly making his way to the front. His forte is authentic Indian design as it should be and there is a tremendous impact in the primitive, barbaric color of his canvas” [8].

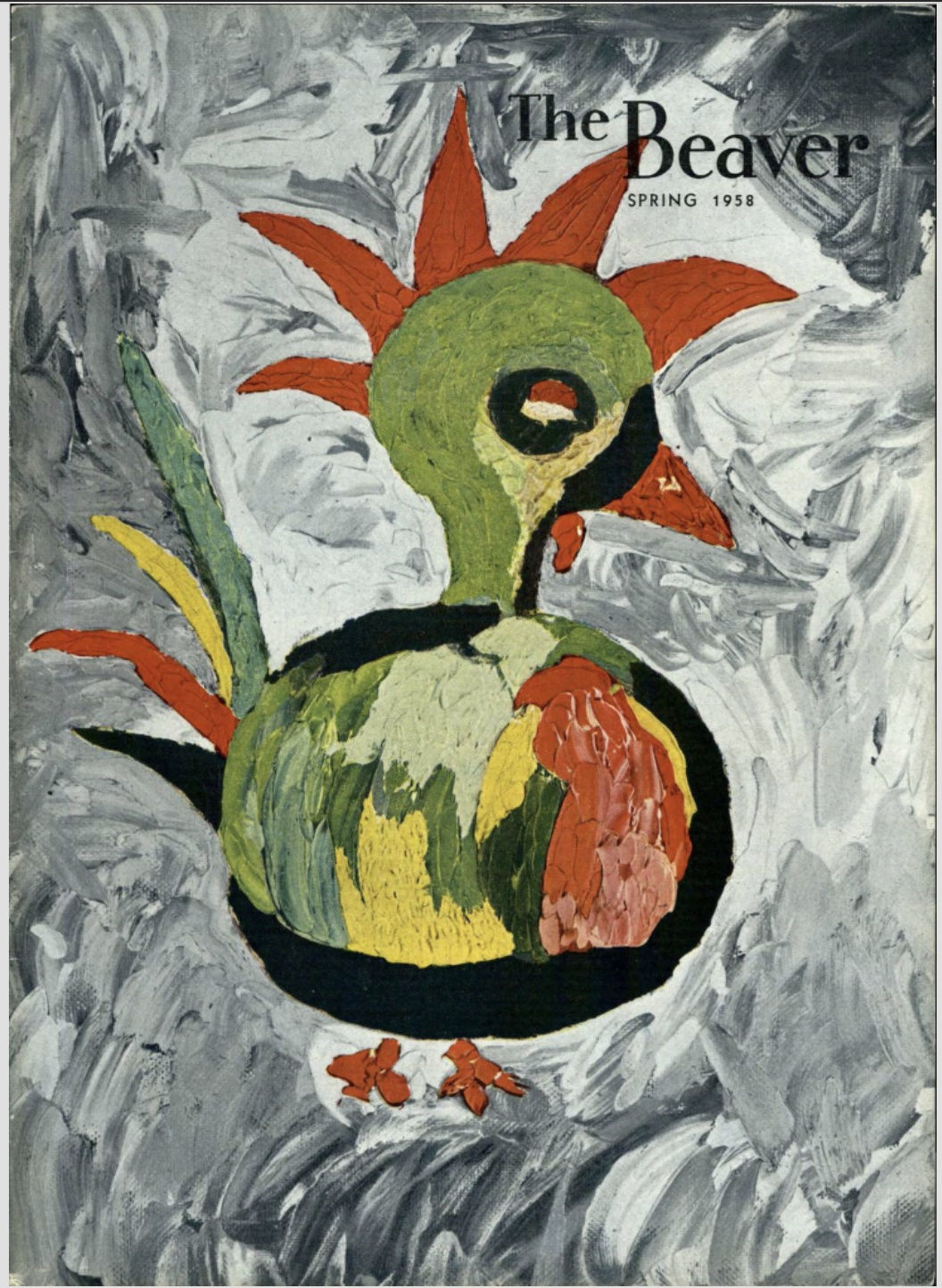

The Spring 1958 cover of The Beaver reproduced a work by Sohaney. The page of contents explains that the cover is a “Painting by Sohaney, Indian name of Jack Douglas Wilkinson, graduate of U.B.C., whose Sioux heritage is clearly discernible in his art” [9].

In March 1958, Jack Wasserman of The Vancouver Sun wrote of the artist’s solo exhibition at Toronto’s Park Gallery. “Jack Douglas Wilkinson, who signs his paintings with his Indian name, ‘Sohaney’ [...] Thirty-two of the artist’s colorful palette knife paintings will be hung in Toronto’s Park Gallery during May for a one-man show, which causes one to wonder why he hasn’t had a show at the Vancouver Art Gallery…” [10]. Although we were unable to confirm the details of this exhibition, Sohaney’s solo exhibition predates Norval Morrisseau’s landmark one man show by four years.

|

|

The Beaver, Spring 1958, with a reproduction of Sohaney’s work on its cover

|

In 1959, Sohaney was solicited by Wallace Sprauge, an affiliate of the New York based publication Parade. Sprauge, after seeing Sohaney’s work on the cover of the December 1958 Abitibi Magazine, "[are] any of your paintings are on display in any New York Gallery and if yes, where I might go to see them? [11]" Sohaney sent the gentleman transparencies of his work, and Sprauge replied, “I like your style and your subject matter and particularly your colouring" [12].

Again in 1959, the Imperial Oil Review discussed the 31 artworks that were selected to be exhibited during a seven month tour of the Western Canada Art Circuit, which travelled to Prince Albert, SK, Calgary, Banff, Kelowna, B.C., Victoria, Edmonton, and Brandon, MB. Of the present oil, the Review author wrote,

There is the primitive vivid splash of Sohaney's ‘Fighting Cocks,’ April, 1957, one of our most popular covers, judging from reader response. (The U.S. Embassy in Ottawa requested a print suitable for framing; 200 reprints were distributed with an issue of Canadian Art Magazine) [13] [14].

Aside from the intriguing, albeit opaque, personal background of the artist, the pictures themselves are outstanding works of art, which prompts us to challenge the obscurity in which the artist's work has, regrettably, languished.

The present six paintings are outstanding and highly keyed. Their interlocking facets of oil are so densely worked that they appear nearly sculptural in form. The pathless interplay of Sohaney’s pigments, though they exude the sense of spontaneity of a work painted au premier coup, are remarkably deliberate. We know of at least one preparatory pen sketch for a landscape by the artist that was shared with Gerry Moses in the Summer of 1957 [15].

It has been our great privilege to research and write about these works. We hope that, in due course, additional scholarship may provide more information about this fascinating artist, whose early works rightfully received such enthusiastic plaudits.

Works Cited

1. Imperial Oil Review, Vol. 41, No. 2., April 1957, inside cover.

2. Indians of the North America, “Indian Time”, Smoke Signals, (Newark, NJ, USA: The Association), Vol. 1, 1951, p. 25

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. Dorothy Livesay, “Indian Magazine Starts Third Year”, The Vancouver Sun, 1 November 1952, p. 22

6. Sohaney, “Editorial”, Indian Time, Vol. 2, No. 9, Sept.-Dec. 1953, p. 3

7. Sohaney “Don’t Ban the Cripple” [Letter to the Editor], The Vancouver Sun, 21 November 1951

8. Smoke Signals, 1951, p. 25

9. The Beaver, Spring 1958, title page

10. Jack Wasserman, “Peeping on People”, The Vancouver Sun, 28 March 1958, p. 29

11. Reproduction, Wallace Sprauge to Sohaney, Private Correspondence, 23 December 1956. We are grateful to the Estate of Barbara Mercer for access to these letters.

12. A handwritten reproduction of the latter from Wallace Sprague to Sohaney, which was sent to Gerry Moses, Private Correspondence, 5 February 1959.

13. “Review in Review,” Imperial Oil Review, Vol. 43, No. June 1959, p. 27

14. Canadian Art Magazine, Autumn 1959.

15. Sohaney to Gerry Moses, Private Correspondence, c. 29 July 1957. We are grateful to the Estate of Barbara Mercer for access to these letters.

First Arts would like to extend our gratitude to the Estate of Mrs. Barbara Mercer for sharing with us the private correspondence between Sohaney and Mr. Gerry Moses.