A skill earned through patience and practice, sewing has been an ever present aspect of life in the Canadian Arctic. The practical efforts could be seen in various parts of daily life: a warm amautiq holding a young child close; a tightly sealed skin kayak bearing a hunter along the water; and mitts and kamiks keeping hands and feet warm and dry. The technical prowess and creativity required to design and sew those necessities of life can clearly be seen in what would become a colourful, expressive art form for Inuit artists: nivingajuliat - or the magnificent works on cloth often referred to simply as “wall hangings.” These beautiful and expressive works have varied subject matter; they often record personal stories, memories of traditional life, and myths and legends, but are also outlets for flights of fancy and pure design. The shapes and forms that an artist used to create visions of both the mundane and the fantastical were only limited by what they could cut and stitch.

In Qamani’tuaq (Baker Lake), a community now synonymous with the art form, the first works on cloth were sewn in the early 1960s, but production began in earnest around 1970, soon after the arrival of the arts advisors Jack and Sheila Butler. Working out of their own homes and then bringing their work to the Craft Shop (an offshoot of the community’s printshop), the first generation of textile artists used wool cloth, felt, and embroidery thread to bring their stories and visions to life.

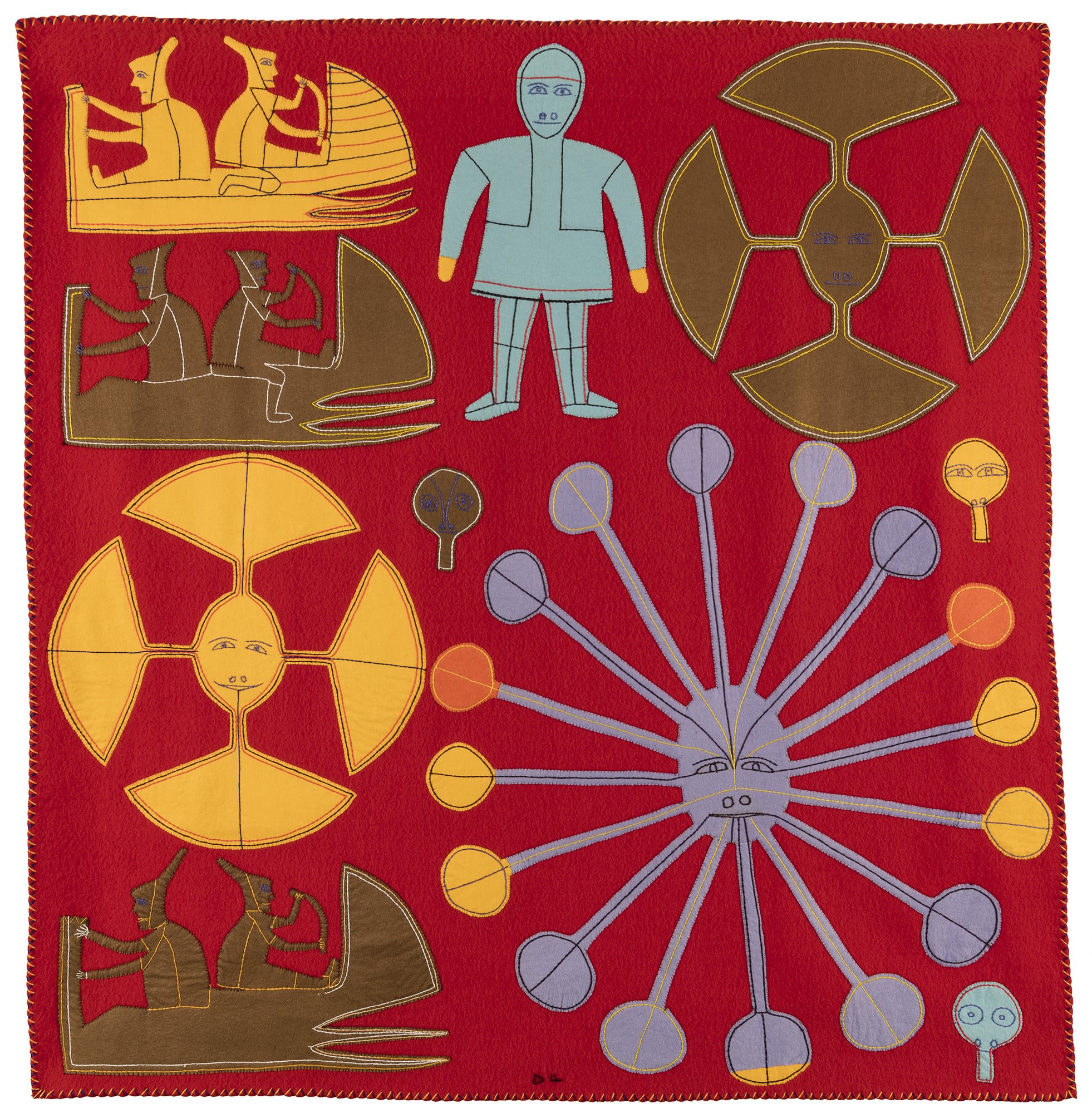

In that first wave of master textile artists, Jessie Oonark’s creative vision stands out; her fusion of traditional life with symbolism and the supernatural is instantly recognizable in her work, be it on paper or cloth. Lot 28, the magnificent Untitled (Composition with Skidoos and Ulus), with its punches of colour on an equally vibrant red background, depicts bursts of ulus and drums radiating from smiling, tattooed faces. In contrast, a highly modern aspect of life in the north is the collection of Skidoos, their skis and windshields sharply outlined in coloured thread.

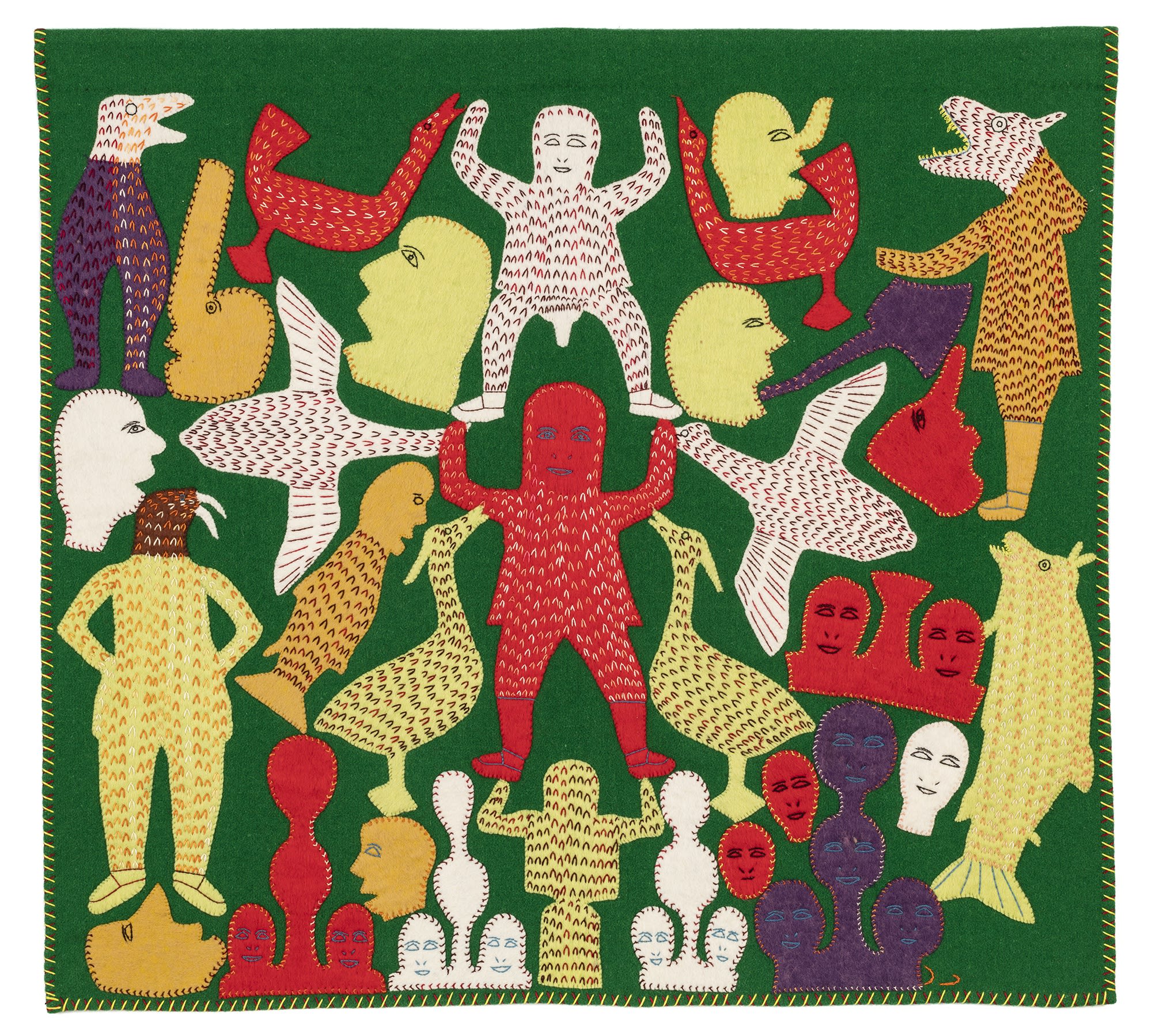

Like many others around her, Oonark anchored her forms to the background with small, tight stitches made of coloured thread that either complimented or contrasted with the felt appliqué. When observed carefully, this can also be seen in the works of one of Oonark’s contemporaries, her cousin Marion Tuu’luq. The two artists differed in technique; where Oonark might further outline and highlight the forms, creating tattoo lines and clothing seams in contrasting colours for example, Tuu’luq would create density and texture in her figures, filling them with fur and feathers.

Never one to leave a sizable portion of a work empty, Tuu’luq often filled her works on cloth with figures in action. In Lot 77, the wonderfully quirky Untitled Work on Cloth (Humans and Spirits), we experience the density of her design, with its delightful jumble of the known and the unknown. Some human forms are spliced with animal features, while some animals have been crossed with others. Many figures in this piece have mouths agape in song or exclamation, and yet silent. We also see a density of stitchery in this work, enlivening many of the felt appliqué shapes. The unadorned background lends stability to the scene, despite the level of detail in the figures.

By contrast Lot 48, a spectacular untitled work by Annie Piklak Taipanak, is a veritable explosion of stitches. Piklak was taught by her mother, the famous seamstress Elizabeth Angrnaqquaq (1916-2003), and was undoubtedly further inspired by others around her. She eventually embraced her mother’s use of embroidery to further decorate works on cloth, and as can be seen here, did so to great effect. There is such depth and texture in both the figures and the spaces between them that one could be forgiven for not even noticing the black stroud behind it all. The feathered and crossed stitches highlight and frame a scene in four panels, perhaps illustrating a story only known to Piklak.

The works of the great artists Oonark, Tuu’luq, and Piklak – and their contemporaries in Baker Lake – truly embody two important concepts: that sewing truly can be an artistic language unto itself; and (to paraphrase Marshall McLuhan) that “the medium can be both the message delivery system and the message itself.”

References: For further reading about Jessie Oonark’s textile practice see Jean Blodgett and Marie Bouchard, Jessie Oonark: A Retrospective (Winnipeg: Winnipeg Art Gallery, 1986), cats. 50-51, pp. 118-119, cat. 56, p. 123, and cat. 76b, p. 132. For Marion Tuu’luq’s work, see Jean Blodgett, Tuu'luq / Anguhadluq: An Exhibition of Works by Marion Tuu'luq and Luke Anguhadluq of Baker Lake (Winnipeg: Winnipeg Art Gallery, 1976), and Laughing at Men with Big Noses from 1978 in Marie Bouchard and Marie Routledge, Marion Tuu’luq (Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada, 2002), cat. 19, p. 68. For a look into wall hangings as conveyors of traditional knowledge, see Krista Ulujuk Zawadski, “Threading Memories” in Inuit Art Quarterly (Spring 2020, Vol. 33, No. 1), pg. 30-39. For more about works on cloth from Baker Lake (including the technical aspects of stitchery) see Katharine W. Fernstrom and Anita E. Jones, Northern Lights: Inuit Textile Art from the Canadian Arctic (Baltimore: Baltimore Museum of Art, 1994).

Lot 28

JESSIE OONARK, O.C., R.C.A.

Untitled (Composition with Skidoos and Ulus), c. 1971-72

wool duffle, felt, cotton thread and embroidery thread, 53 x 50.75 in (134.6 x 128.9 cm)

ESTIMATE: $40,000 — $60,000

Lot 77

MARION TUU'LUQ, R.C.A.

Untitled Work on Cloth (Human and Spirits), c. 1988-89

stroud, felt, embroidery floss and cotton thread, 26.25 x 29.25 in (66.7 x 74.3 cm)

ESTIMATE: $18,000 — $28,000

Lot 48

ANNIE PIKLAK TAIPANAK

Untitled Work on Cloth, 2004

stroud and embroidery floss, 72 x 57.5 in (182.9 x 146.1 cm)

ESTIMATE: $7,000 — $10,000