Wooden model poles emerged in the early 1870s as a category of souvenir on the Northwest Coast that was often collected, at least early on, by whalers and Navy crewmen. Currently, the oldest confirmed date for a wooden model pole is 1870, for a Tlingit piece in the collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. [1] By around 1900, it’s arguable that, along with baskets, these miniature sculptures had become the predominant form of Northwest Coast artworks made for sale. Model pole production continued to ramp up for the first half of the 20th century, peaking in the postwar tourism boom of the 1950s and 1960s, before being rapidly replaced by more culturally grounded, fine art oriented objects that were made for and sold in galleries. All told, the heyday of model pole production lasted for around a century. Although the oldest examples and model poles from well-known makers such as Charles Edenshaw (Haida, 1839-1920) and Willie Seaweed (Kwakwaka'wakw, 1873-1967) have always been sought by collectors, the last 15 years or so has seen a large increase in interest and demand for works by artists who have been identified through academic research and attribution. [2]

First Arts is pleased to offer five fine examples of model poles that span this era of production in our forthcoming December 2, 2024, sale.

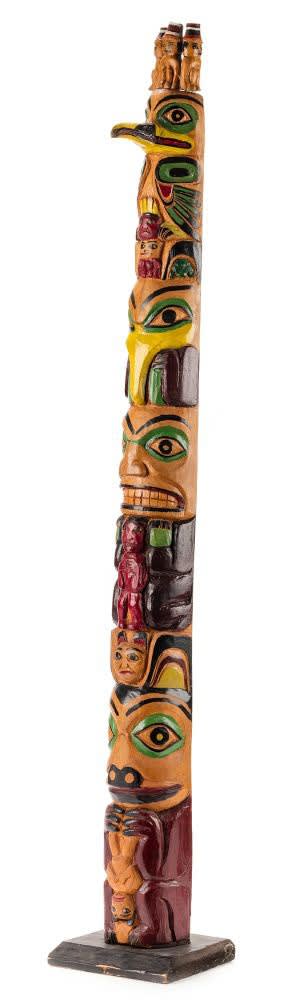

The earliest pole being offered in our upcoming sale is a Tlingit model that likely dates to the 1870s or 1880s. There are several hints for this earlier date of production, including the attention paid to the faces of the figures, the usage of indigenous mineral paints including what looks like a copper-based blue/green, Chinese vermilion, and bone black, and the hollowing out of the back of the pole. Additionally, the looser application of paint on the pole is more aligned with earlier, customary Tlingit objects.

Lot 97

UNIDENTIFIED TLINGIT ARTIST

Model Hollow Back Totem Pole, c. 1870s or 1880s

ESTIMATE: $8,000 — $12,000

View Images and details

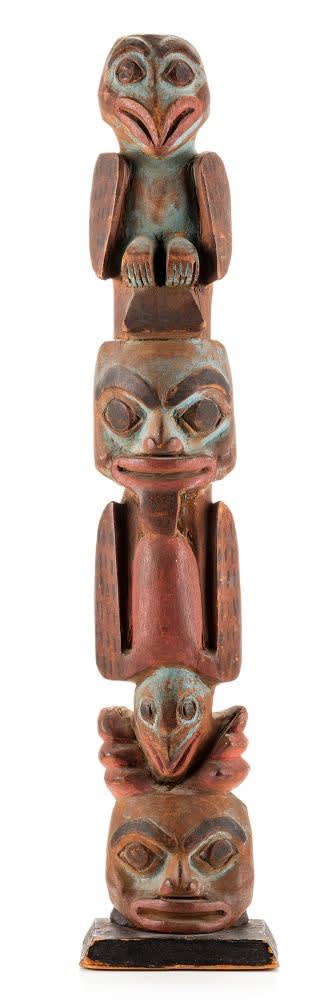

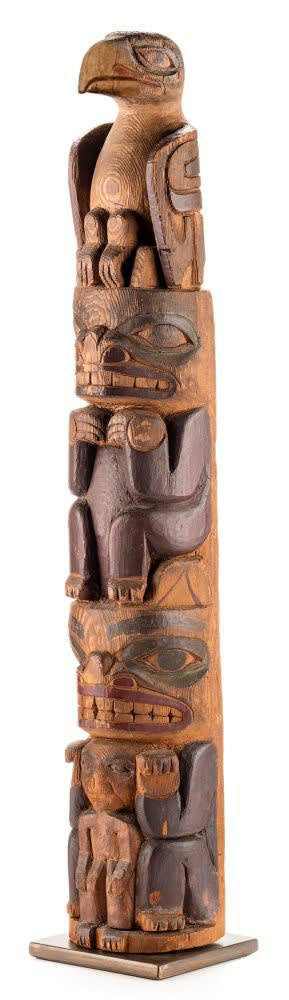

The next two poles are by William James Ukas (Tlingit, 1834-1902) and Robert Ridley (Haida, 1855-1934). Both of these artists were Northern master carvers born in the mid-19th century, who made monumental poles in a professional capacity before making model poles for sale later in their lives. Their experiences likely played a role in the ability of both of these carvers to capture the monumentality of full-sized poles in a miniature scale, something that later model pole makers often struggled with. In the case of the Ukas pole, the model is scaled so well that it almost looks like a maquette, which is not surprising, given that Ukas was also the carver of the monumental pole it is based on. With the Ridley model, there is a real substantive presence to his carving and an attention to proportion within and between the figures that recalls his monumental sculpture.

Lot 106

WILLIAM JAMES UKAS (YEEKA.AAS) (1834- c. 1902), TLINGIT

Raven Totem (Kiks.ádi) Model Pole, c. 1890-1900

ESTIMATE: $7,000 — $10,000

View Images and Details

Lot 144

ROBERT RIDLEY (1855-1934) HAIDA

Model Totem Pole, c. 1910-1915

ESTIMATE: $3,000 — $5,000

View Images and Details

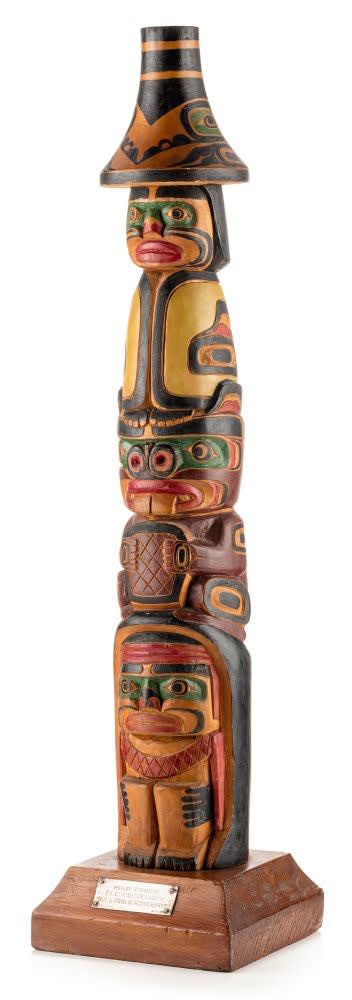

The fourth pole being offered is by Kitselas Tsimshian carver Titus Campbell (1893-1966), an artist who was most active in the mid-20th century. Campbell was from the first generation of model pole carvers who consistently signed their work. Consequently, Campbell was well known to collectors within his lifetime and continues to be a sought-after maker today. It likely helped that Campbell often worked for William Webber’s Thunderbird/Scenery Shop in Vancouver and for the Totem Pole Gift Shop in Prince Rupert, British Columbia, where this pole originated. [3] Campbell was a skilled carver who was able to create pieces in a number of regional styles, including Tsimshian, Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw, and Haida. This pole is a combination of his Tsimshian and Haida styles and depicts a historic pole from the village of Ninstints, on Haida Gwaii. Campbell’s work was finely sculptured and featured a preponderance of paint coverage that reflects the influence of fellow Tsimshian carver Frederick Alexcee (c.1857-c.1944) on his work.

Lot 128

TITUS CAMPBELL (1893-1966), TSIMSHIAN, KITSELAS

Model Totem Pole (Prince Rupert / Poles), 1940s

ESTIMATE: $3,500 — $5,000

View Images and Details

The fifth and final model pole is by Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw master carver Henry Hunt (1923-1985). Henry is a hugely important artist from a historically significant Indigenous family. Henry was the grandson of Tlingit ethnographer George Hunt (1854-1933), the son-in-law and apprentice of Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw artist Mungo Martin (1879-1962), and the father of artists Tony Hunt Sr. (1942-2017), Richard Hunt (b. 1951), and Stanley Hunt (b. 1954). This pole is an early and especially fine example of Henry’s work and really reflects Martin’s influence on his art. It’s especially nice and a bit unusual that the pole is fully carved and painted, particularly for it being made in the 1950s. Often, poles made in that time period would either be fully carved or fully painted, but rarely both. Also, the Chief figure, Beaver, and Hamatsa Dancer are all motifs that Henry would revisit throughout his career, so this pole also provides some interesting insight into how his style and artwork evolved over time.

Lot 127

HENRY HUNT SR. (1923-1985), KWAKWA̱KA̱ʼWAKW

Model Totem Pole, c. 1957-58

ESTIMATE: $4,000 — $6,000

View Images and Details

Notes

1. Robin K. Wright, Skidegate House Models: From Haida Gwaii to the Chicago World’s Fair and Beyond (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2024), p. 6.

2. For more on this, see chapter and list by this author in Carvings and Commerce: Model Totem Poles, 1880-2010 (2011), Zachary R. Jones’ dissertation Haa Léelk’w Hás Ji.Eetí, our Grandparents’ Art: A Study of Master Tlingit Artists, 1750-1989 (2018), and Robin K. Wright’s Skidegate House Models: From Haida Gwaii to the Chicago World’s Fair and Beyond (2024).

3. William Webber’s collection of model poles and ephemera is housed in the Museum of Vancouver and heavily features artworks by Campbell, which give a good idea of his stylistic range and output during this time.

Christopher W. Smith