Introduction

Throughout the Canadian Arctic, drawing has remained an especially important medium for artists, who have pursued the genre regularly, and with ingenuity. This exhibition explores the transformation of the medium of drawing in the settlement of Qamani’tuaq by the artists of the first and second generations and the ways in which they pushed the boundaries of artistic production.

For the structure of this exhibition, we are entirely indebted to Marion Jackson, who was the first to present the drawings of the Qamani’tuaq artists with a decidedly academic approach. Jackson first explored Qamani’tuaq drawings in her PhD dissertation in 1985 and in 1995, she expanded on her thesis for the catalogue produced for the MacDonald Stewart Art Centre’s travelling exhibition, Qamanittuaq (Where the River Widens): Drawings by Baker Lake Artists. In addition to providing valuable information on the origins of the settlement of Qamani’tuaq, which we have discussed elsewhere, Jackson suggests a theory of the differences between the first and second generation of artists in Qamani’tuaq, which remains one of the most succinct and inspired ways of looking at the drawings produced in Qamani’tuaq for the period of 1960 to the 2000s. We have chosen to present the works in this exhibition with Jackson’s framework in mind.

Nadine Di Monte

COVID-19 Viewings & Condition Reports

First Arts continues to monitor the developments related to the COVID-19 virus outbreak, including adherence to the recommendations of provincial guidelines. Our first priority is to continue to act in the best interest of our community to ensure the safety of our staff, clients, and vendors. At this time, no in person previews are available. Our experts are happy to show works, answer your questions, and provide virtual consultations by video call. In addition, our team can provide thorough and comprehensive condition reports and additional images. We welcome your enquiries at info@firstarts.ca or 647-286-5012. The absence of condition does not imply that an item is free from defects, nor does a reference to particular defects imply the absence of any others.

-

FIRST GENERATION ARTISTS

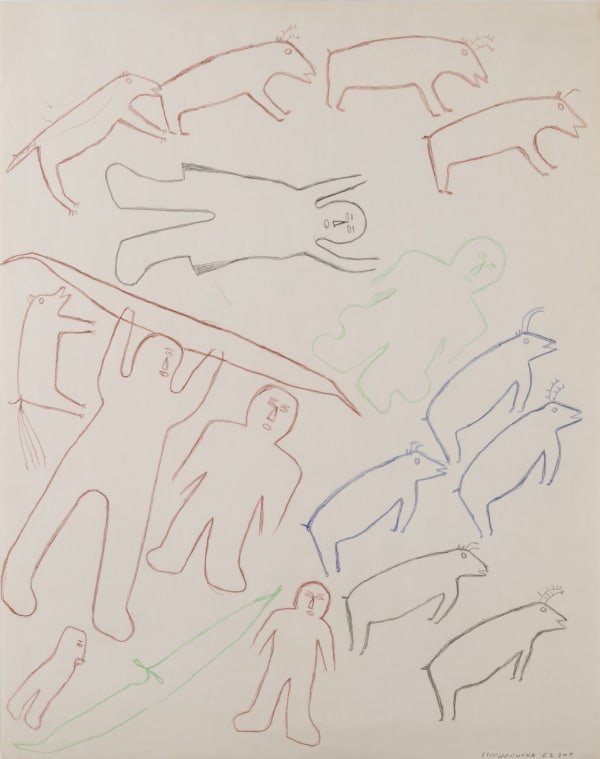

With limited connection to southern standards of art making, the first generation of Qamani’tuaq artists made works guided largely by their own compulsions. Though each artist developed their own unique style of communicating their subject matters, similarities emerge in looking at the body of works created in the settlement. The First Generation of Qamani’tuaq artists — represented in this show by Luke Anguhadluq, Martha Ittulaka’naaq, and Jessie Oonark — hailed from remote areas in the Kivillaq region. Oonark and Anguhadluq, both Utkuhikhalingmiut from the Back River and Chantrey Inlet area were connected by marriage. Martha Ittulaka’naaq, likely of Harvaqtuurmiut descent, was from the Kazan River area. All three were young children when the Hudson’s Bay Company opened its trading post in 1916, several kilometers away from where they were residing. It was not until around 1960 when the three would relocate to Qamani’tuaq. As these artists grew to maturity living a traditional lifestyle that was much similar to that which sustained their ancestors for generations previous, representations of traditional tools and activities are chief among their chosen motifs. Their inland location meant that caribou, hare, fish, birds, and muskoxen are represented in abundance, with very few depictions of coastal marine animals. Spiritual aspects of traditional culture are depicted, broadly speaking, in scenes of the drum dance but, again, given their orientation, do not feature the Talelayu figure. While the three have much in common, their visual language is solely their own. Seemingly unfettered but what art ought to look like, each of the drawings of these artists are characterized by a purity of spontaneous expression.

-

-

LUKE ANGUHADLUQ (1895-1982) QAMANI’TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)

LUKE ANGUHADLUQ (1895-1982) QAMANI’TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)Caribou with Dogs and Geese, 1975

coloured pencil on heavy wove BFK Rives watermarked paper, 22 x 30 in (55.9 x 76.2 cm)

View Details -

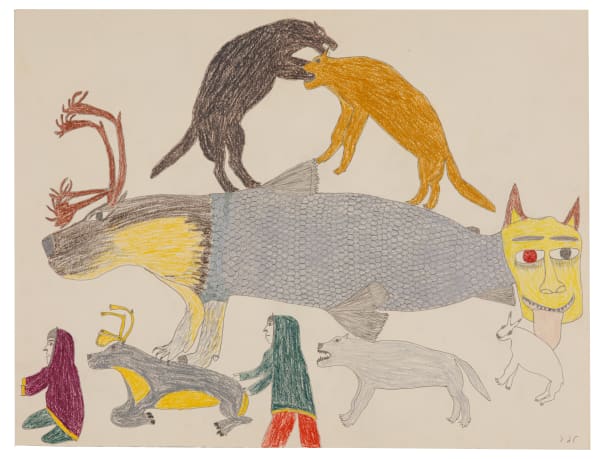

LUKE ANGUHADLUQ (1895-1982) QAMANI’TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)

LUKE ANGUHADLUQ (1895-1982) QAMANI’TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)Plentiful Catch, c. 1970

coloured pencil on thin wove paper, 24 x 19 in (61 x 48.3 cm)

View Details

-

-

Luke Anguhadluq

The drawings of Luke Anguhadluq, represented in this show with three works, show keen observational skills and considerable imagination. Anguhadluq’s rugged style draws us — none too gently — into his fertile memories. All three works represented in this show illustrate Anguhadluq’s unconventional approach to scale and perspective. In Caribou with Dogs and Geese, 1975, we encounter a frenetic and densely populated scene of a caribou hunt that presents its cast of characters from all different orientations. In the central scene, we see two men, each of a slightly different scale, approaching a caribou, whose red tongue juts out to suggest that it is bellowing a defensive bleat. The trio can be easily read as being presented in profile but the flanking figures are more difficult to interpret. Nine birds, each composed in Anguhadluq’s gestural lines of coloured pencil, are depicted from a distinctly ariel vantage point, save one that is shown in profile. In the top left corner, three dogs of a similar size are shown in different arrangements. Depending on how we read the image, only one is positioned upright, while the others have been drawn so that they appear to hover upside down in midair. As the entire image is devoid of a background, Anughadluq has, perhaps unconsciously, allowed us to complete the image through our own understanding.

-

-

MARTHA ITTULUKA'NAAQ (1912-1981) BAKER LAKE (QAMANI’TUAQ)

MARTHA ITTULUKA'NAAQ (1912-1981) BAKER LAKE (QAMANI’TUAQ)The Old Way of Hunting, c. 1970

coloured pencil on thin wove paper, 24 x 19 in (61 x 48.3 cm)

View Details -

MARTHA ITTULUKA'NAAQ (1912-1981) BAKER LAKE (QAMANI’TUAQ)

MARTHA ITTULUKA'NAAQ (1912-1981) BAKER LAKE (QAMANI’TUAQ)The Old Way of Living, c. 1970

coloured pencil on heavy wove paper, 13 x 8.5 in (33 x 21.6 cm)

View Details

-

-

MARTHA ITTULUKA'NAAQ

Martha Ittulaka’naaq, too, channelled her own memories into impactful compositions. As with Anguhadluq’s works, Ittulaka’naaq’s pictorial strategy resists any easy orientation and lets us be guided by our own intuitions. We can explore her works piecemeal. As one grouping leads to another, there is seemingly no end to the ever changing events that we are seeing.

In the first two works shown, Old Way of Hunting and Old Way of Living, the figures are composed of boldly coloured straight lines that swing into curves, which float on the sheet like stout, airy structures. In the Old Way of Hunting , motifs of the hunt — primarily caribou and kayaks — are jostled together in a lively, imaginative manner. In the Old Way of Living, nestled amongst similar views of the hunt, is a figure with a drum.

-

-

![JESSIE OONARK, O.C., R.C.A (1906-1985) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE) Christ Figure Offering Liquid [“This cup is the new covenant in My blood; ; do this, as often as you drink it, in remembrance of Me.”…], 1976 coloured pencil on wove paper, 14 x 9.5 in (35.6 x 24.1 cm)](data:image/gif;base64,R0lGODlhAQABAIAAAAAAAP///yH5BAEAAAAALAAAAAABAAEAAAIBRAA7) JESSIE OONARK, O.C., R.C.A (1906-1985) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)

JESSIE OONARK, O.C., R.C.A (1906-1985) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)Christ Figure Offering Liquid [“This cup is the new covenant in My blood; ; do this, as often as you drink it, in remembrance of Me.”…], 1976

coloured pencil on wove paper, 14 x 9.5 in (35.6 x 24.1 cm)

View Details -

JESSIE OONARK, O.C., R.C.A (1906-1985) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)

JESSIE OONARK, O.C., R.C.A (1906-1985) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)Camp Scene, late 1960s

coloured pencil and felt tip on heavy wove paper, 14.75 x 9.5 in (37.5 x 24.1 cm)

View Details

-

-

SECOND GENERATION ARTISTS

For the Second Generation of artists, relocation to Qamani’tuaq came at an earlier, more formative age. The great strength of the second generation artists — represented in this exhibition by Nancy Pukingrnak Aupaluktuq, Victoria Mamnguqsualuk, and Janet Kigusiuq, Oonark’s daughters; Janet’s husband, Mark Uqayuittuq; Hannah Kigusiuq, Harold Qarliksaq, Simon Tookoome, Françoise Oklaga, Irene Avaalaaqiaq Tiktaalaaq, Myra Kukiiyaut, and Ruth Annaqtuusi Tulurialik —is their ability to merge their absorption of imagery from life on the land with life in the settlement and to synthesize these diverse sources into visual languages that were entirely their own.

-

-

-

-

JANET KIGUSIUQ (1926-2005) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)

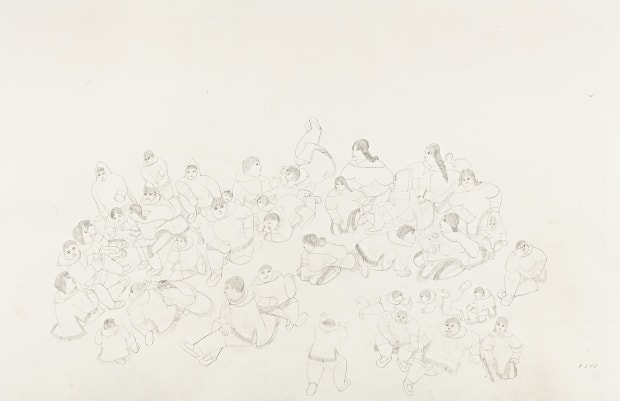

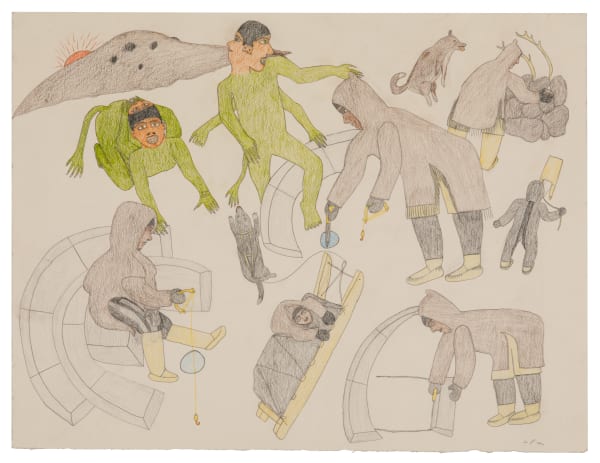

JANET KIGUSIUQ (1926-2005) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)Busy Camp Life (Traditional Activities) 1975

graphite coloured pencil on heavy wove BFK Rives watermarked paper, 22 x 30 in (55.9 x 76.2 cm)

View Details -

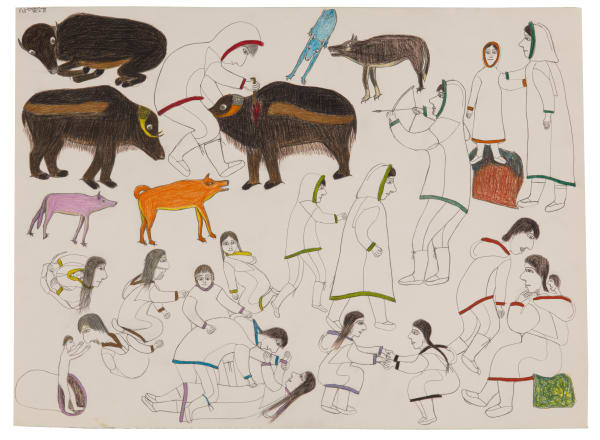

JANET KIGUSIUQ (1926-2005) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)

JANET KIGUSIUQ (1926-2005) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)Camp Scene with Drum Dance, Woman Sewing, and a Feeding Dog, mid-late 1970s

graphite and coloured pencil on heavy wove paper, 22.5 x 28.25 in (57.1 x 71.8 cm)

$ 1,200.00View Details -

JANET KIGUSIUQ (1926-2005) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)

JANET KIGUSIUQ (1926-2005) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)Jovial Camp Scene, mid-late 1970s

graphite and coloured pencil on heavy wove BFK Rives watermarked paper, with Sanavik Cooperative Association embossed blindstamp, 22 x 29.75 in (55.9 x 75.6 cm)

$ 1,200.00View Details -

JANET KIGUSIUQ (1926-2005) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)

JANET KIGUSIUQ (1926-2005) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)Playing a Winter Game

graphite and coloured pencil on heavy wove Arches watermarked paper, 22.25 x 30 in (56.5 x 76.2 cm)

View Details

-

JANET KIGUSIUQ (1926-2005) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)

JANET KIGUSIUQ (1926-2005) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)Inuk with Quarrelling Sled Dogs

coloured pencil and dry medium on heavy wove paper, 22 x 30 in (55.9 x 76.2 cm)

View Details -

JANET KIGUSIUQ (1926-2005) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)

JANET KIGUSIUQ (1926-2005) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)Safe Inside the Igloo

dry medium and coloured pencil on cerlox bound thin wove paper, 17 x 13.75 in (43.2 x 34.9 cm)

View Details -

JANET KIGUSIUQ (1926-2005) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)

JANET KIGUSIUQ (1926-2005) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)Waiting in a Summer Tent

dry medium and coloured pencil over graphite on cerlox bound thin wove paper, 18 x 23.75 in (45.7 x 60.3 cm)

View Details -

JANET KIGUSIUQ (1926-2005) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)

JANET KIGUSIUQ (1926-2005) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)Man, Woman, and Dogs Approach Two Polar Bears

coloured pencil on heavy wove paper, 22.25 x 30 in (56.5 x 76.2 cm)

View Details

-

JANET KIGUSIUQ (1926-2005) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)

JANET KIGUSIUQ (1926-2005) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)Father and Son Conversing in a Landscape

coloured pencil on on cerlox bound thin wove paper, 23.75 x 18 in (60.3 x 45.7 cm)

$ 1,600.00View Details -

JANET KIGUSIUQ (1926-2005) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)

JANET KIGUSIUQ (1926-2005) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)Portrait of a Family

coloured pencil on heavy wove paper, 22.25 x 30 in (56.5 x 76.2 cm)

$ 1,600.00View Details

-

-

JANET KIGUSIUQ

Like Qarliksaq, Janet Kigusiuq, Jessie Oonak’s eldest daughter, moved to Qamani’tuaq at the urging of the Canadian government to see that her children attend the newly constructed schools. Represented in this exhibition by ten works, these drawings illustrate not only her prolific output but her transition from figural works to highly abstracted landscapes

In the first five works shown above, the sheets positively teem with the depictions of camp life in Kigusiuq’s dynamic pictorial style, which Cynthia Waye, in her solo exhibition on the artist, referred to as quite complex [17]. Each of these five works contain scores of figures that are drawn with assured graphite lines and ornamented with scant but deft touches of colour to accent their garments. The introduction of larger swaths of colour is primarily used to decorate animals, inanimate objects, and the very occasional piece of clothing. Two of the smaller works, Safe Inside the Igloo and Waiting in a Summer Tent, feature the same essential stylistic drawing methods but their mood is a much softer one of private interiority.

In the latter three works, we are introduced to what would prove to be Kigusiuq's signature style of draughtsmanship: employment of colour in a decidedly architectural maner. Blocks of heavily coloured pigment establish the contours of her still internally blank figures. A liberally drawn expanse of black, for example, aids to delineate the form of one of the polar bears in Man, Woman, and Dogs Approach Two Polar Bears. The effect of this unique style of optical drawing is one that is, to our eye, missing from her strictly landscape works of the 2000s.

-

-

MARK UQAYUITTUQ (1925-1984) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)

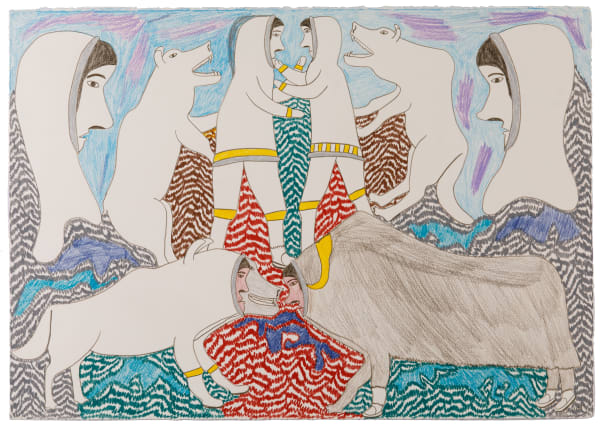

MARK UQAYUITTUQ (1925-1984) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)Sea Spirits at Play, c. 1976

coloured pencil and graphite on heavy wove paper, 19 x 26 in (48.3 x 66 cm)

View Details -

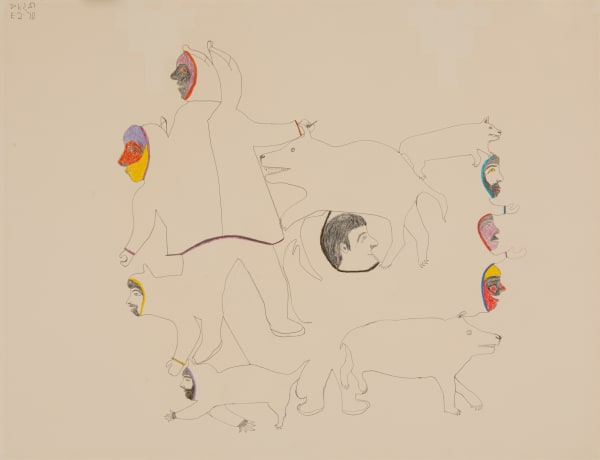

MARK UQAYUITTUQ (1925-1984) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)

MARK UQAYUITTUQ (1925-1984) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)Shamans Transforming, 1970s

graphite and coloured pencil on heavy wove paper, 20 x 26 in (50.8 x 66 cm)

View Details

-

-

Mark Uqayuittuq

Mark Uqayuittuq was the adopted son of Luke Anguhadluq. He was also married to Janet Kigusiuq, with whom he created a personal sign language as Uqayuittuq, himself, was deaf and mute. Although his body of work, from a numbers perspective, is nowhere near comparable to that of his wife, there are stylistic similarities between the two, best seen in Shamans Transforming. As with Kigusiuq, the bulk of the figures in this maze of erupting beasts that resist any easy identification are composed of simple graphite lines and adorned with small touches of colour. Sea Spirits At Play is similar in subject to many of the celebrated prints and drawings of Uqayuittuq’s mother in law, Jessie Oonark.

-

Irene Avaalaaqiaq Tiktaalaaq

After recovering from tuberculosis, Irene Avaalaaqiaq relocated permanently to Qamani’tuaq in the fall of 1958 but only began her artistic career in the late 1960s / early 1970s, at the encouragement of the Butlers. Almost exclusively, Avaalaaqiaq’s inspiration for her works comes from her desire to visualize the stories told to her as a child by her grandmother. Avaalaaqiaq told Judith Nasby, “‘The stories my grandmother told me are from the time when animals used to talk like human beings. [... She] used to tell me about an animal that could turn into a man and a man that could turn into an animal [18]” Each of the six works by Avaalaaqiaq in this exhibition reflect her preoccupation with the animal and/or human hybrid creatures of these narratives.

In the first three works shown, we see figures that retain a distinctly human appearance but with subtly adopted bird-like traits. This bird-human motif appears so often in Avaalaaqiaq’s works that Judith Nasby wrote that the image of hybridized bird-human figures “crops up, almost like a signature, in many of her works [19].” Avian figures appear also in Spirit Figure in a Cartouche where Avaalaaqiaq has cleverly manipulated the negative space of her black sheet to simultaneously describe frontal human faces and birds with open beaks in profile. We see the bird motif again in Alternating Creatures Surrounded by Humans and Birds, wherein the torrid pink border ripples and swells at the left and right with bird and human faces in profile. The central four figures of this work recall the beasts featured in her Avaalaaqiaq’s work Fighting Creatures, 1999 in the collection of the Art Gallery of Guelph. The artist explained that the hybrized creatures were either half fish, half human, or half wolf, half fish [20].

In Human / Muskox in a Landscape, Avaalaaqiaq deviates entirely from the feathered creature to depict a different composite human-animal character. Set a midst a colourful landscape, we see an ambling beast whose muskox body features windswept wool drawn in electric yellow and its human face composed of an equally vibrant pink.

-

-

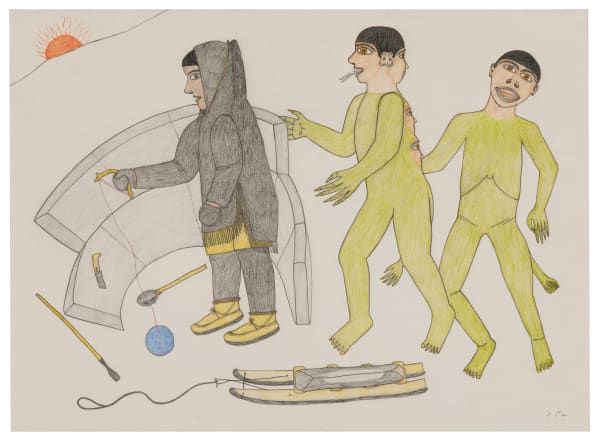

NANCY PUKINGRNAK AUPALUKTUQ (1940-) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)

NANCY PUKINGRNAK AUPALUKTUQ (1940-) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)Monstrous Creatures Approach Fisherman, c. 1976

coloured pencil on heavy wove BFK Rives watermarked paper, 22 x 30 in (55.9 x 76.2 cm)

View Details -

NANCY PUKINGRNAK AUPALUKTUQ (1940-) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)

NANCY PUKINGRNAK AUPALUKTUQ (1940-) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)Monstrous Creatures Terrorize the Fish Weir, c. 1976

coloured pencil on heavy wove paper, 20 x 26 in (50.8 x 66 cm)

View Details -

NANCY PUKINGRNAK AUPALUKTUQ (1940-) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)

NANCY PUKINGRNAK AUPALUKTUQ (1940-) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)Two-Faced Monsters Torment People and Dogs, 1976

coloured pencil on heavy wove BFK Rives watermarked paper, 22 x 29.5 in (55.9 x 74.9 cm)

View Details -

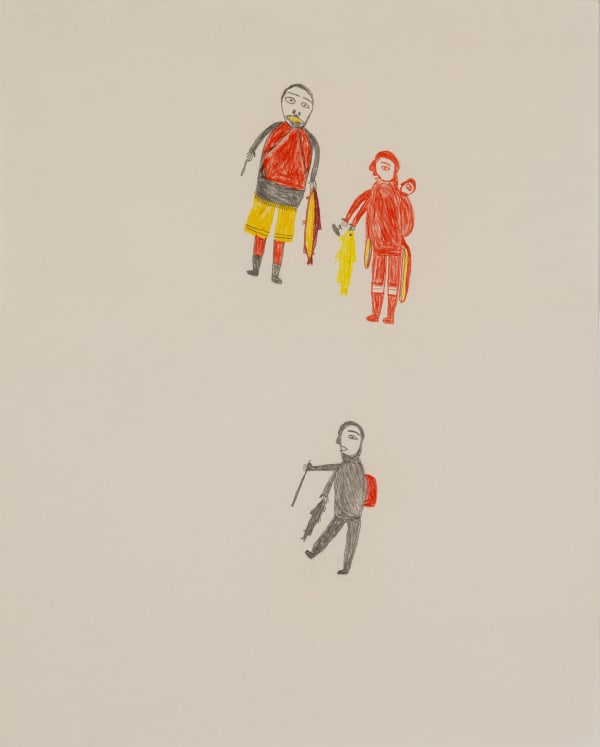

NANCY PUKINGRNAK AUPALUKTUQ (1940-) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)

NANCY PUKINGRNAK AUPALUKTUQ (1940-) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)Father Teaching Son to Hunt Caribou, 1978

graphite and coloured pencil on heavy, wove BFK Rives watermarked paper, 29 x 22 in (76 x 56 cm)

View Details

-

-

Nancy Pukingrnak Aupaluktuq

The youngest daughter of Jessie Oonark, Nancy Pukingrnak Aupaluktuq relocated to the settlement of Qamani’tuaq in her late teenage years. Though she had been drawing regularly since the 1970s, only five of her works were included in the annual print collections from Qamani’tuaq, one of which, Rescued from Two-Faced Monsters, featured the same multi-faced humanoid monsters that we see in the first three drawings illustrated above. Monstrous in form and electric green in colour, these creatures, Pukingrnak explained, were simply birthed from her imagination. “One time I was making a soapstone carving [...] and the stone had lumps on the back of it [like faces] [21].” Elsewhere, Pukingrnak explained that the creatures were an expression of her angst ridden pathos. Of a similar work, she said, “This I drew out of my own mind. I am scared a lot and this is a scary scene [22].”

In striking contrast to these disquieting visions of monsters, is Father Teaching Son to Hunt Caribou. The careful construction of this ambitious composition provides a detailed description of a young boy learning to capture caribou with his father. While similar in subject to her predecessors, unlike the first generation artists, there is a clear attempt by Pukingrnak to illustrate spatial depth in her work. In her 1985 dissertation, in which this work is reproduced as figure 49, Marion Jackson gives a detailed and superb description of the present work, which reads,

Pukingnak’s recent drawing of a father teaching his son to hunt caribou (fig. 49) evokes the sense of a benevolent and harmonious natural order [...]. The soft, light colours of Pukingnak’s naturalistic landscape are applied in evenly controlled strokes. A light blue sky with fluffy white clouds and a full sun provide an idyllic setting in which ground squirrels frolic and birds flutter, establishing a pastoral contact for the main action of Pukingnak’s drawing. The primary figures are a wounded but passively immobile standing caribou and a father and son whose placid expression and languid gesture belie the violence of the action about to occur. The gray knife in the father’s right hand is nearly obscured by the brown-gray landscape, and neither he nor the caribou which stands obsequiously before him give any evidence of the [...] struggle in which they are engaged. Pukingnak captures and expresses the harmonies of nature through the quiet harmonies of her drawings [23].

-

-

SIMON TOOKOOME (1934-2010) QAMANI’TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)

SIMON TOOKOOME (1934-2010) QAMANI’TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)Shaman Flanked by Men and Dogs, 1978

coloured pencil on heavy wove BFK Rives watermarked paper, with with Sanavik Cooperative Association embossed blindstamp, 22 x 30 in (55.9 x 76.2 cm)

VIew Details -

SIMON TOOKOOME (1934-2010) QAMANI’TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)

SIMON TOOKOOME (1934-2010) QAMANI’TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)Hunters Pursued by Dogs

coloured pencil on heavy wove Arches watermarked paper, 22.25 x 30 in (56.5 x 76.2 cm)

VIew Details -

SIMON TOOKOOME (1934-2010) QAMANI’TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)

SIMON TOOKOOME (1934-2010) QAMANI’TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)Inuit, Dogs and Shamans Transforming, c. 1996

coloured pencil on heavy, wove paper, 21 x 29.5 in (53.3 x 74.9 cm)

VIew Details -

SIMON TOOKOOME (1934-2010) QAMANI’TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)

SIMON TOOKOOME (1934-2010) QAMANI’TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)The Spirit of Preys, c. 1979

coloured pencil on heavy wove paper, 20 x 26 in (50.8 x 66 cm)

VIew Details

-

-

Simon Tookoome

Preoccupied primarily with aesthetics, Simon Tookoome’s drawings are often skilled arrangements of splendid symmetry. This disciplined sense of balance is seen in all four of the present works and in particular in Shaman Flanked my Men and Dogs, wherein the figures are arranged in a near perfectly mirrored composition. We are impressed with the same reflective symmetry in Hunters and Dogs and Inuit, Dogs, and Shamans Transforming but also by the way inwhich Tookoome has filled his entire page with illustration. In these two aforementioned works, rapid, angular strokes infuse the scene with a vibrating energy.

The final two works presented above, while still harmoniously balanced compositions, stand quite apart from the others. One of the latest arrivals to Qamani’tuaq, Tookoome was in his mid 30s before he settled in the community in 1969. As a result, Marion Jackson suggests, the subject of hunting, in addition to being a common subject of the first generation of artists, was a favourite of the artist as well [24]. The way inwhich Tookoome presented interpretations of this common theme, however, differs dramatically from his predecessors. In Spirits of Preys, the animals subject to the hunt are treated in a wholly unique and rather dreamlike fashion. What seems a fixed scene begins to shift and never quite yields to a specific naming of what is represented. In Homeward Bound, as we see in Hunters and Dogs and Inuit, Dogs, and Shamans Transforming, the entire sheet is filled with mixed media marks by Tookoome but here the figural elements are subordinated by the landscape. Silhouettes of humans done in sketchy black ink strokes dot the undulating hills, beckoning home the green hooded hunter in the distance.

-

-

-

-

RUTH ANNAQTUUSI TULURIALIK (1934-) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)

RUTH ANNAQTUUSI TULURIALIK (1934-) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)Drying Fish at the Weir

coloured pencil on heavy wove paper, 22.25 x 30 in (56.5 x 76.2 cm)

View Details -

RUTH ANNAQTUUSI TULURIALIK (1934-) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)

RUTH ANNAQTUUSI TULURIALIK (1934-) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)Tattooed Woman Speaks of the Spring Camp, 2004-5

coloured pencil over graphite, 14 x 17 in (35.6 x 43.2 cm)

View Details -

RUTH ANNAQTUUSI TULURIALIK (1934-) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)

RUTH ANNAQTUUSI TULURIALIK (1934-) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)Fishing at the Gloam

coloured pencil over graphite, 14 x 17 in (35.6 x 43.2 cm)

View Details -

RUTH ANNAQTUUSI TULURIALIK (1934-) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)

RUTH ANNAQTUUSI TULURIALIK (1934-) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE)On the Land, 2004-5

coloured pencil over graphite, 14 x 17 in (35.6 x 43.2 cm)

View Details

-

-

RUTH ANNAQTUUSI TULURIALIK

Ruth Annaqtuusi Tulurialik, was born in the Kazan River area but was adopted as an infant by Thomas Tapatai, the assistant to the Anglican missionary, Canon James. Living so nearby to Qamani’tuaq from a young age, Annaqtuusi’s works offer a rather unique perspective than those of her contemporaries. Her proximity to the settlement meant that in addition to her contact with the qallunaq in Qamani’tuaq, Annaqtuusi encountered many individuals from the disparate subcultures of the Kivillaq region who would first visit the trade centres in the settlement before any permanet relocation to Qamani’tuaq. Boldly presented, highly complex, and brilliantly colourful her graphic works are imagined recollections of the customs and stories of her culture that speak to a sense of preservation. In a 1986 interview she said, “We can show that our ancestors used to do things a certain way, even if we won’t do it the same way [25].

-

Works Cited

1. After the creation of Nunavut in 1999, the Keewtain Region became the Kivalliq Region, with only slightly different boundaries.

2. With an increased interest in white fox furs, the first trading post was established at the southside of Qamani’tuaq in 1916 by the Hudson’s Bay Company. The Anglican and Roman Catholic churches established mission posts in Qamani’tuaq in 1926 and 1927, respectively. In 1946, during WWII, as part of “Operation Muskox,” the Royal Canadian Air force built an base in Qamani’tuaq. A weather station was built in 1947.

3. Though the subgroups within the Kivallirmiut classification are similar in many respects, they differ rather significantly in many ways, including contact with quallunaq. The Harvaqtuurmiut and Paallirmiut remained inland throughout the year and were the most isolated. The Qainigmiut (Qaernermiut) came in the summer months to the coast to trade with whalers and other visitors. The Utkuhiksalingmiut had cultural similarities with the central Kivallirmiut as well as the Netsilingmiut. We encourage anyone interested in further information on the subject to consult Marion Jackson’s 1985 dissertation and her 1995 contribution to the catalogue, Qamanittuaq (Where the River Wides): Drawings by Baker Lake Artists.

4. Other settlements include: Arviat [Eskimo Point], Tikiraqjuaq [Whale Cove], Kangiqliniq [Rankin Inlet], Igluligaarjuk [Chesterfield Inlet], Salliq [Coral Harbour], and Naujaat [Repulse Bay]

5. Marion E. Jackson, Baker Lake Inuit Drawings: A Study in the Evolution of Artistic Self-Consciousness, University of Michigan, PhD Dissertation, 1985, p. 72

6. The first generation of artists in Qamani’tuaq were affiliated with ten cultural sub-groups. The largest segment of the population at this time held ancestral ties with the Netsilingmiut: the Utkuhiksalingmiut, the Ualingmiut, the Saningayukmiu, and the Iluiliaqmiut. The next largest population segment, composed of the Qainigmiut (Qaernermiut), the Akilinirmiut, the Harvaqtuurmiut, the Tariaqmiut, and the Paallirmiut, which have ancestral ties to the Kivallirmiut. Finally, representing a relatively small portion of the population were member sof the Aivilingmiut, whose heritage stems from the Iglulingmuit

7. The potential for artistic production in the area had been documented before. In 1947, during “Operation Muskox,” two service men suggested that the Inuit in the region should be encouraged in art making. Dr Andrew MacPherson and Edith Dodds recognized Oonark’s talents early on. The latter would send a handful of Oonark's drawings to Kinngait to be made into prints for inclusion in the 1960 and 1961 annual print catalogues. Having sold the rare c. 1958-9 drawing by Oonark, we now know that the schoolteacher Bernard Mullen, indulged Jessie in her artistic whim.

8. Helga Goetz, The Inuit Print, exh. cat., (Ottawa: National Museum of Man, 1972), p. 192

9. Ibid.

10. Judith Nasby, Marion E, Jackson, et. al, Qamanittuaq: Where the River Widens, (Guelph, ON: Macdonald Stewart Art Centre, 1995), p. 35

11. Kotelowitz’s efforts to get the print shop up and running were most admirable. First, he recognized the extraordinary talent of Jessie Oonark and provided her a stipend and study to create her drawings. After searching for suitable stone with which to make print blocks, he could not locate dynamite to excavate the stone. He placed an order for the explosives but, in the interim, spearheaded a crew to drill the stone out to no avail. By the time the ordered dynamite arrived, the snow had melted and there was no way to transport the rock from the quarry to the settlement.

12. Nasby / Jackson, 1995, p. 36

13. In the author’s opinion, the importance that Jack and Sheila Butler played in artistic production cannot be overstated. The pair contributed not only to the creation of the print shop but assisted in seeing renewed interest in textile works and secured the necessary materials for tapestry making. Their business savvy secured a $50,000 federal loan for the creation of the Sanavik Cooperative.

14. George Swinton, Baker Lake Prints 1972, (Qamani’tuaq: Sanavik Cooperative, 1972), unpaginated.

15. Ibid.

16. Jackson, 1985, p. 213

17. Cynthia Waye, The Urge ofAbstraction: The Graphic Art of Janet Kigusiuq, exh. cat., (Toronto: Museum of Inuit Art, 2008), p. 6

18. Judith Nasby, Irene Avaalaaqiaq: Myth and Reality (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2002), p. 56

19. Ibid., p. 70

20. Ibid., p. 95, pl. 18

21. Nasby / Jackson, et. al, 1995, p. 123.

22. Ibid., p. 124

23. Jackson, 1985, p. 198

24. Ibid.

25. Kirk LaPointe, “Inuit artist’s drawings reflect the changing times,” Calgary Herald, 4 March 1986, p. F1

![JESSIE OONARK, O.C., R.C.A (1906-1985) QAMANI'TUAQ (BAKER LAKE) Christ Figure Offering Liquid [“This cup is the new covenant in My blood; ; do this, as often as you drink it, in remembrance of Me.”…], 1976 coloured pencil on wove paper, 14 x 9.5 in (35.6 x 24.1 cm)](https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_600,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/firstarts/images/view/8a6b0e43a5cfb8253b83784d8c3bf684j/firstarts-jessie-oonark-o.c.-r.c.a-1906-1985-qamani-tuaq-baker-lake-christ-offering-wine-at-the-last-supper-1-corinthians-11-25-1976.jpg)