Kinngait Studios have long been acclaimed for their standout printmaking program. However, only recently has their hand-printed textile initiative from the 1950s and 60s in Cape Dorset garnered the recognition it deserves.

As with the prints produced in the same era, the textiles reveal a diverse array of inspirations and influences, namely, the Inuit graphic tradition, the preferences of the southern art market, the dominant graphic design sensibilities of the time, and the influence of Japanese block and stencil printing.

In the first work offered in our forthcoming September Online Auction, likely a test print by Sorosiluto Ashoona, we see a celebration of Arctic avian fauna. While their arrangement may appear spontaneous at first glance, the artist’s deliberate design becomes evident on close inspection. Each flaxen-coloured feathered figure is meticulously positioned in a choreographed pattern that fills the linen ground. If the primary requirement of a pattern is to hold the eye, this design’s allure stems from its order; even when it appears to be random, there's uniformity in its irregularity. Sorosolitu's fabric is subtly representational. While the figures are unmistakably birds, they are presented as flat golden silhouettes with organically flowing plumage, giving the design an unusually cerebral quality and feel of abstraction.

Attributed to: SOROSILUTO ASHOONA (1941-) KINNGAIT (CAPE DORSET)

Title Unknown (Many Golden Birds) (Probably a Test), c. 1965

ESTIMATE: $350 — $500

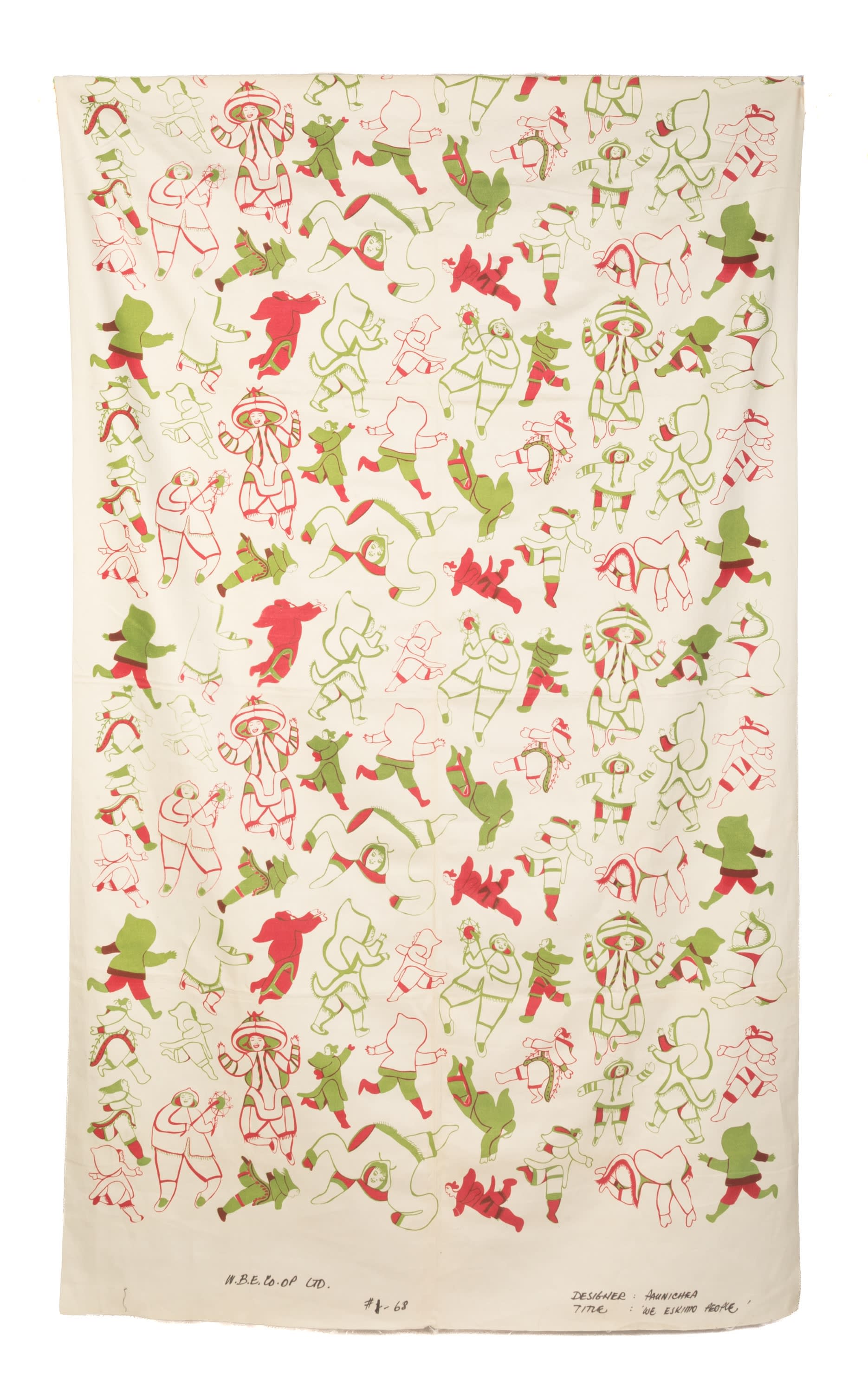

In the next work by Pitseolak Ashoona, We Eskimo People, in a mosaic of green and red, the artist highlights the spirit of Inuit joy. Scores of figures come together harmoniously, evoking the sense of a celebration. Some figures beat skin drums, while others contort in dance poses, skip, or confidently execute handstands. The joyous energy that radiates from the textile is a testament to both the celebratory spirit of the Inuit and the artistic prowess of Pitseolak Ashoona.

As both pattern elements, broadly speaking, highlight human figures engaged in leisurely pursuits, in this printed textile by Pitseolak, we see echoes of the 18th-century Toile de Jouy patterns. However, while the elements of We Eskimo People are distinctly representational, their spatial arrangement and graphic flatness evoke an abstract pattern and Pitseolak has created her design with considerably more airy abandon. The design captivates with its harmonious blend of structured order and unpredictable rhythm.

PITSEOLAK ASHOONA, R.C.A., O.C., (1904-1983) KINNGAIT (CAPE DORSET)

We Eskimo People (Probably a Test Print), c. 1965

ESTIMATE: $500 — $800

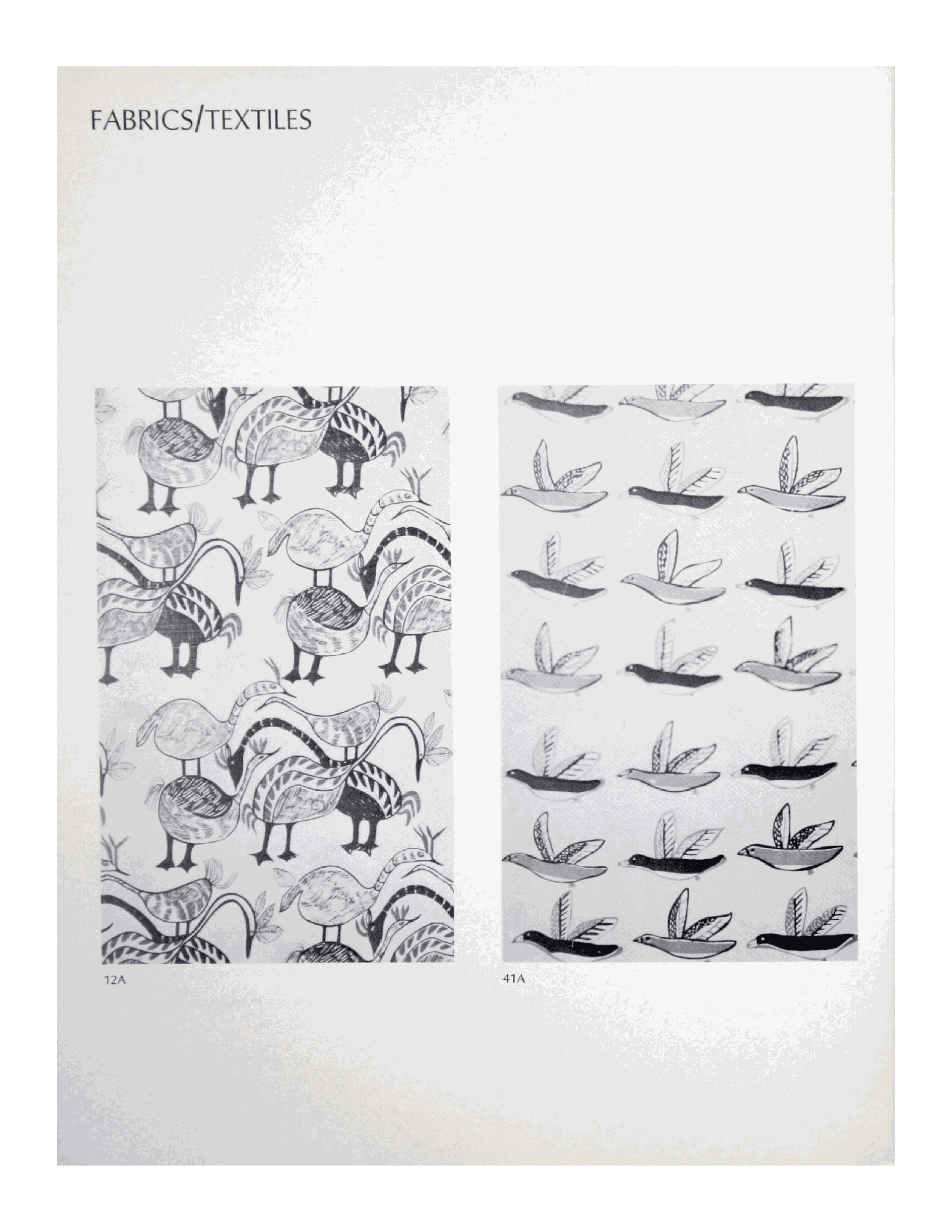

In Arctic Birds, we encounter a recurring motif in the artist’s works. According to Christine Lalonde, of her more than 8,000 drawings, more than half of Pitseolak’s drawings include birds as the primary subject [1]. While the artist has made no explicit indications on her repeated use of birds in her artworks, they may be interpreted as symbols of movement and the natural world. They can also represent the interconnectedness of life in the Arctic, where animals play a crucial role in survival. The intricate cross hatched lines on each of her five birds echo the design elements found in Pitseolak’s etchings and engravings, which were created at the encouragement of Terry Ryan in the early and mid-1960s, linking this particular textile to another era of artistic experimentation in Kinngait [2].

While Arctic Birds presents clearly representational elements, Pitseolak’s composition and graphic simplicity meld effortlessly with the printmaker’s design to exude a sense of breezy freedom, striking a captivating balance between orderly structure and unexpected rhythm, which culminates in a splendid overall pattern.

PITSEOLAK ASHOONA, R.C.A., O.C., (1904-1983) KINNGAIT (CAPE DORSET)

Title Unknown (Arctic Birds), c. 1965

ESTIMATE: $500 — $800

Kinngait's Experimental Textile Years

While Inuit-made cloth artworks are globally recognized and celebrated, there has not been a central emphasis on textile creations from Kinngait until rather recently. In the early days of artistic production in Kinngait, under the direction of James and Alma Houston, Inuit women were encouraged to leverage their skills as seamstresses. Artists like Kenojuak Ashevak created sealskin appliqued hangings, dolls, handbags (see First Arts, 5 December 2022, Lot 146), and other utilitarian objects such as beaded parkas, mitts, and slippers.

While Kinnait Studio’s textile forays remain less documented, in her essay for the 1991 catalogue for the exhibition at the McMichael, In Cape Dorset We do it this Way: Three Decades of Inuit Printmaking, Leslie Boyd writes,

In late 1957 the first printmaking experiments began. They were probably intended to pave the way for the manufacture of printed products, such as hand-blocked fabrics using Inuit designs [3].

While Boyd did not expand on this experimental program, in foreword for the 1980 Cape Dorset print catalogue, Virgina Watt shares a quote from the minutes of a 1956 meeting with the Board of Directors of the Canadian Handicraft Guild, which reads,

Mr. Houston plans to teach twelve Eskimos [sic] to make stone blocks for use in hand blocking yard goods. The designs will be native in character and with possibly one exception, these students will not be drawn from the well known carvers. In due course, Mr. Houston proposes to send examples of this work for exhibition purposes only. Mr. Houston showed the members fabric samples blocked with some of the designs he contemplates using [4].

While much has been documented about the experimental stonecuts and stencils on paper from the time frame of 1956-1957, there is, regrettably, little information on the textile initiative of this period. We do know that photographer S. Smith was contracted by the then Department of Northern Affairs and Natural Resources to take still images of the artists engaged in the various art programs in Kinngait for photographs that were be to included in the landmark showing at the Stratford Festival in July 1959 [5], including the below image that shows a number of the printmakers at work created a hand-printed textile [Fig. 1].

From left, Osuitok Ipeelee, James Houston, Kananginak Pootoogook and Lukta Qiatsuk developing a stencil on fabric in the Spring of 1959.

After the success of the 1959 Cape Dorset graphics collection, marketing initiatives appear to have focused on graphic production exclusively. However, James Houston remained invested in the textile initiative. As revealed in the important 2021 exhibition catalogue, Printed Textiles from Kinngait Studios, Houston corresponded with William “Mac” Berry of the Primary Textiles Institute of Montreal. Roxane Shaughnessy and Anna Richards share how the two engaged in discussions about the best techniques and fabrics for the project [6].

Kinngait's Textile Shift in the sixties

As Houston was exiting the Arctic in 1962, in the summer of 1963 Olga Chajkowsky [7] was hired to teach the printmakers in Kinngait “how to screen sketches from paper on to fabric” [8]. An unaddressed letter from Berry in October 1964 suggests that Terry Ryan continued the dialogue and that Berry was optimistic about the prospect of screen printing on fabric, writing that stone block printing “would not be practical but plans for a screen printing show prospects of a successful application of Eskimo [sic] designs…” [9].

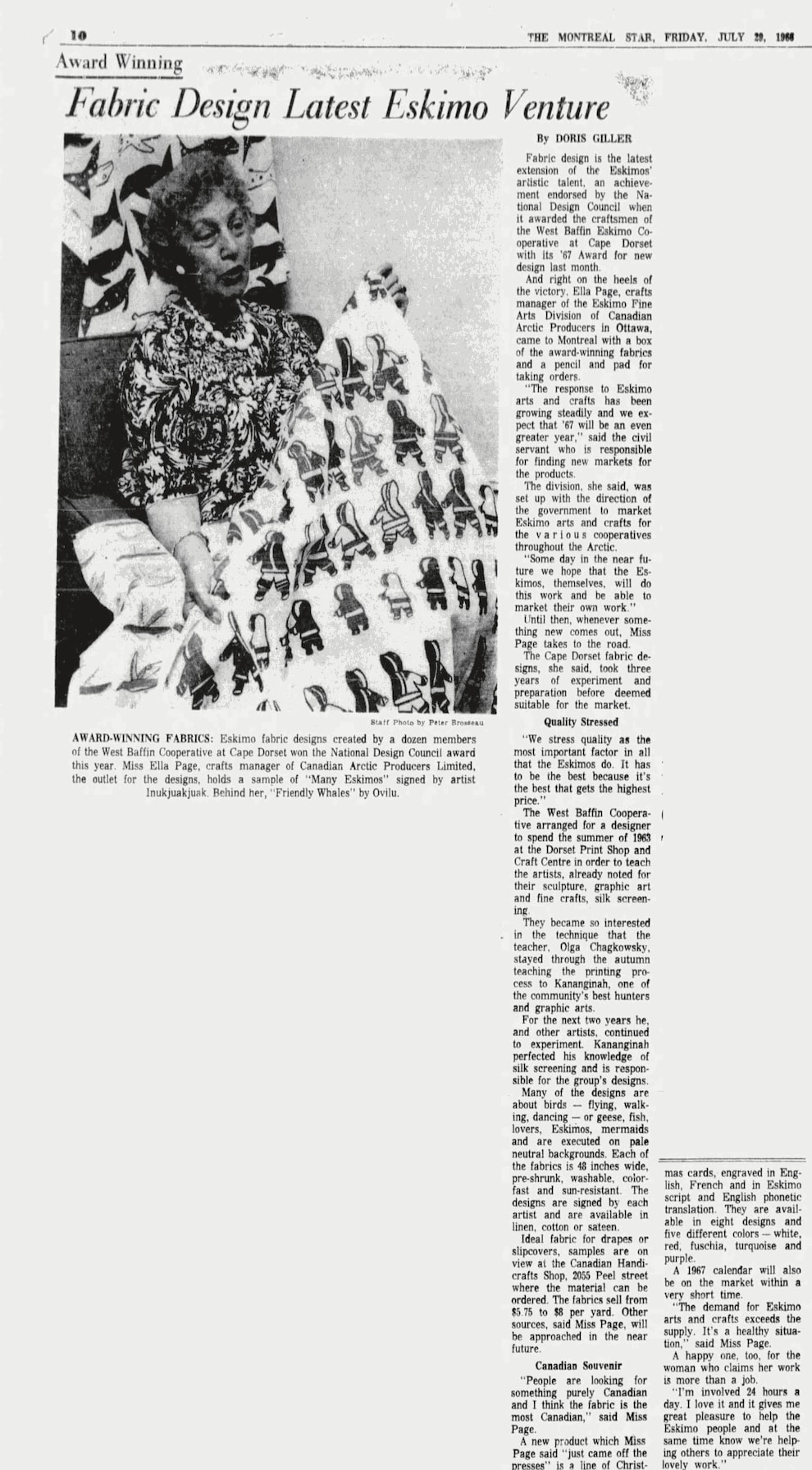

In the mid-1960s, following significant trial and error, Terry Ryan started marketing the printed fabrics to a southern audience. These fabrics were publicly received with great acclaim, a sentiment cemented by their victory of the Design ‘67 Award [Fig 2]. Roxane

The Design ‘67 Program received 2,400 submissions: 1,300 in the existing product category and 1,100 in the new product design category. Of these, 650 existing and 410 new were accepted. The WBEC fabrics were accepted into the new product category and were one of 58 products to win an award for exceptional new design. The award-winning new products were given monetary awards intended ‘to help defray the costs of prototype development.’ The WBEC received a $1,000 award, sponsored by the National Design Council. The other award winners were given prizes ranging from $200 to $1,500 per design; only 14 of the designs were awarded $1,000 or more, suggesting that the Kinngait fabrics represented some of the best and most promising designs in the competition [10].

Fig 2.

Clipping, Doris Giller, “Award Winning Fabric Design Latest Eskimo Venture,” The Montreal Star, 29 July 1966

Despite plans for Kinngait fabrics to be included in the Indian and Eskimo Pavilion at Expo '67, their actual presence seems to have been limited. They did, however, find a stage in architect Moshe Safdie’s “Habitat '67” condo building in Montreal. In an image reproduced in Printed Textiles from Kinngait Studios, one of Anernik’s textile designs can be seen hanging in a suite, that was curated by Barbara MacLennan [Fig. 3] [11].

Fig. 3

Interior of a suite of “Habitat ‘67” with Anernik’s Fabulous Geese hung at upper left.

Reproduced in Roxane Shaughnessy & Anna Richards, Printed Textiles from Kinngait Studios, (Toronto: Textile Museum of Canada, 2021), Figure 22, p. 43, as

“Design Canada: Canadian Design at Expo 67. National Design Council”.

Fig 4.

Clipping, “New art dimension wins awards,” The Leader Post, (Regina, Saskatchewan), 22 July 1966, p. 6

Kinngait’s Textile Legacy: Conclusion

The journey of hand-printed works on cloth in Kinngait, running parallel to the revered printmaking initiative of Cape Dorset in the late 1950s and 60s, offers a vivid exploration into the heart of Inuit artistry and innovation. These textiles, a confluence of diverse inspirations from traditional Inuit graphics to the nuanced influences of the southern art market and Japanese printing techniques, stand as a testament to Inuit adaptability and creativity. While their intricate designs, such as those by Sorosiluto Ashoona and Pitseolak Ashoona are globally recognized for their vibrant depictions of life and culture, their history remains intriguingly understated, with only the recent exhibition at Toronto’s Textile Museum highlighting their importance in the history of at production in Kinngait.

The passion and dedication of the contributing artists, as well as figures like James and Alma Houston and Terry Ryan, coupled with the relentless pursuit of technique refinement and market strategies, laid the foundation for these textiles. However, like many pioneering endeavours, they faced challenges of recognition, sustainable production, and market viability. Despite these setbacks, their legacy persists, embodied in ventures like Inunoo that continue to celebrate and adapt the Inuit graphic tradition. This narrative not only shines a spotlight on the brilliant and often overlooked fabric initiative but also serves as a poignant reminder of the resilience, evolution, and profound cultural significance of Inuit art in the broader tapestry of global artistic heritage.

First Arts is greatly indebted to Roxane Shaughnessy and Anna Richards for the structure and content of this essay. Those interested in the history of Kinngait hand printed textiles are encouraged to read Printed Textiles from Kinngait Studios.

End notes

Comments

I wonder if someone might not look at resuscitating the old designs, or commission new ones, to be used commercially for bedding or kitchen linens.

Thank you for bringing this to our attention.