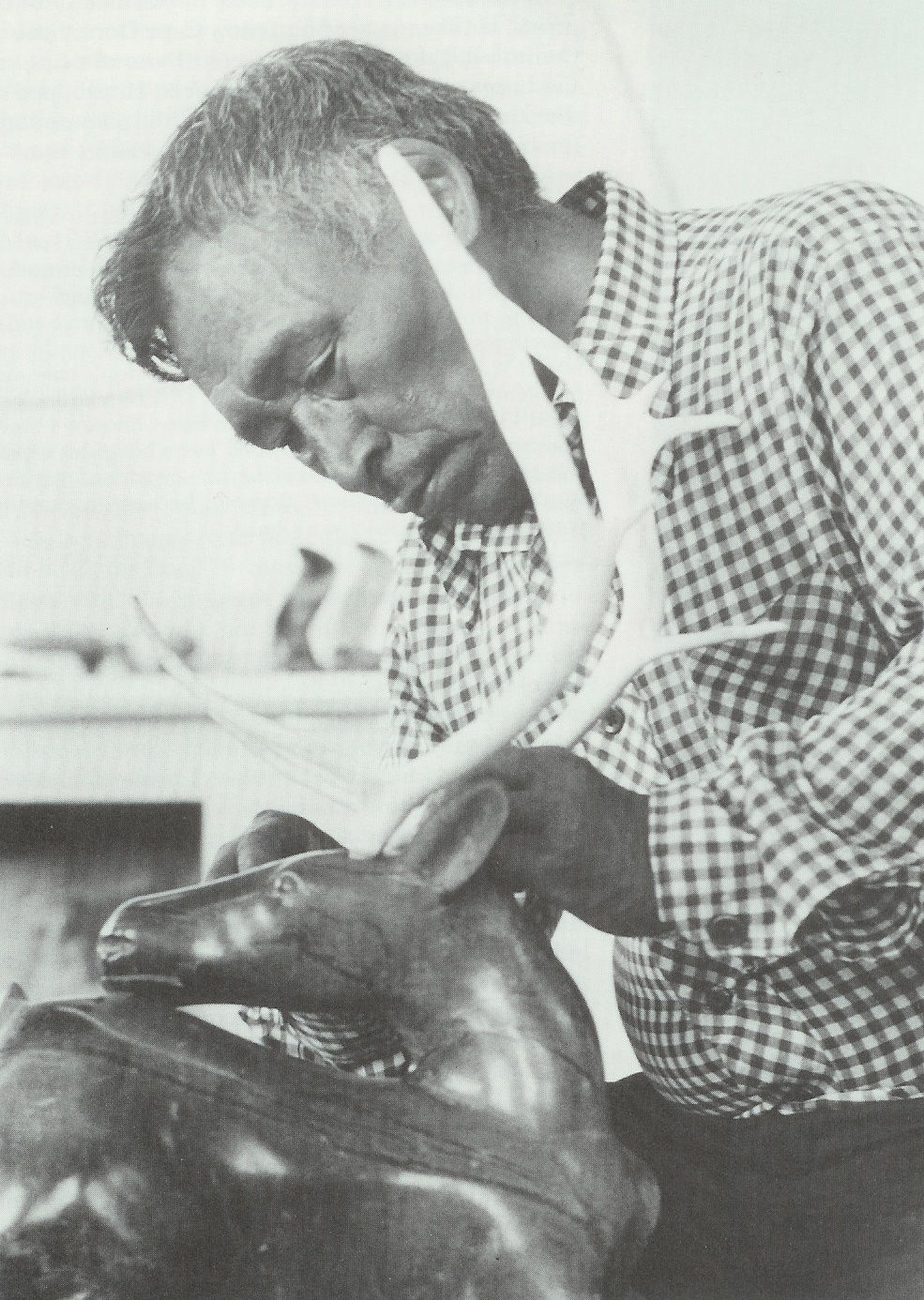

Portrait of Osuitok Ipeelee by Jimmy Manning, for Jean Blodgett, “Osuitok Ipeelee” in Alma Houston, ed., Inuit Art: An Anthology.

Osuitok Ipeelee was born at Neeouleeutalik camp on southern Baffin Island and lived a traditional hunting life for decades. His father was killed by a shaman when Osuitok was only twelve years old, and as one of the older sons – two of his siblings were the future artists Sheokjuk and Innuki Oqutaq – much responsibility fell upon him to help support the family. Osuitok reminisced about his teenage years in 2004:

I remember the time the RCMP, the Hudson’s Bay Company and the Catholic Priest came here. The Bay was the first, a trading post. I used to help them out when they needed help. If they wanted to go to camping areas, I would take them. When I was a teenager, I used to have a dog team. I had three dogs and would go everywhere. I would go from camp to camp to see how people were doing, to see if they had enough food. If they didn’t, I would give some to them. Some were starving and I gave them food. I would go trapping and I would get lots of fox and take them to the traders. That is the only place you could take your furs. The trading post had the only white people in town when I was a teenager. (In Ingo Hessel, Arctic Spirit, 2006, p. 150)

Clearly, Osuitok was not afraid of hard work or challenging situations. It is also apparent that he was not only devoted to high-level craftsmanship in his art, but he was also quite an entrepreneur. Having carved wooden toys by the age of thirteen, Osuitok began making and selling carved and incised ivory works already in the 1940s while in his twenties, and encouraged by James Houston, he started to carve stone in the early 1950s. Osuitok was not particularly prolific in the 1950s but in the early 1960s he was soon recognized as Cape Dorset’s preeminent sculptor, and today is considered by many to be the greatest Inuit sculptor of all time. Certainly, in Cape Dorset he set the standards for workmanship and imagination and daring that we associate with the community’s sculptural style. He was – and still is – the artist most emulated and the one that the other sculptors dreamed of surpassing. Yet Osuitok did not stand still, he loved to move back and forth between different subjects and styles, always looking for new challenges:

I’ve always tried to make different kinds of carvings, not to do the same things over and over again like some carvers do. Some carvers make one carving which is very popular and then tend to make the same carving over and over even though they are fairly famous carvers. I try to make a lot of varieties of carving. (Osuitok interviewed by Dorothy Eber in “Talking with the Artists” in In the Shadow of the Sun, 1993, pp. 439-340.)

Osuitok was not satisfied simply to change up his subject matter. His technical mastery of stone is legendary; like a magician, he seemed to be able to make stone bend and stretch to his will. Furthermore, the scope of his visual imagination is truly impressive. Osuitok was a carver of works of breath-taking naturalistic beauty one week, and a daring abstract sculptor the next. Many of his creations benefited greatly from his firsthand knowledge of Arctic animals and their behaviour, but Osuitok’s true genius lay in his ability to transform his animal subjects – caribou, birds, and other animals – into stylized objects of his imagination.

John Westren, who has worked for Dorset Fine Arts and the Kinngait Studios for more than thirty-five years, wrote an eloquent article on the sculpture of Osuitok in the Inuit Art Quarterly. His description of Osuitok’s brand of naturalism beautifully summarizes his artistic vision and his unique gifts as a sculptor. “Ipeelee often spoke of the real. To make something look real involved more than replicating the surface appearances of a subject. It was to express an ideal. He achieved this quality in his sculptures by carving areas of animals or human figures deliberately disproportionate to emphasize the parts that give the subject energy, vitality, meaning and emotion.” [1] A brilliant example of this can be seen in his Standing Caribou from the 1980s (Lot 15).

Osuitok was a frank admirer of the female form, and depictions of women fishing or engaged in daily chores were by far his favourite human subjects, extending as far back as the 1950s. Osuitok’s female figures share a lovely sense of tranquillity but also a sense of purpose. These qualities are beautifully conveyed in Mother and Child, Scraping a Skin from c. 1980-82 (Lot 34).

Although many of Osuitok’s sculptures convey a sense of spirituality, he carved relatively few works with overtly shamanic themes. One of his most famous and important examples is Shaman from the mid 1970s (Lot 61). It’s so radically different in style from either the Standing Caribou or Mother and Child, Scraping a Skin that it’s almost difficult to belief that this startling work was carved by the same artist! But in its own way, the work is just as daring as the others.

What the three sculptures share is that they each demonstrate a similar sense of intellectual curiosity and experimentation by their maker. They are imbued with the same unmistakable intelligence and true sense of style that marks the hand of the genius and magician Osuitok.

1. John Westren, “A Quest for the Real: The Art of Osuitok Ipeelee,” Inuit Art Quarterly (Vol. 34.4, Winter 2021:42-51), p. 45.

Lot 15

OSUITOK IPEELEE, R.C.A. (1923-2005), KINNGAIT (CAPE DORSET)

Standing Caribou, mid-late 1980s

ESTIMATE: $35,000 — $50,000

Looking for examples of caribou sculptures by Osuitok to compare with this gorgeous work, we are reminded of one in particular: a stunning Walking Caribou from c. 1987-88 which we had the privilege to offer in our 13 July 2021 auction (Lot 27). In that catalogue essay we wrote: “Osuitok’s vision – his genius – was his ability to idealize his caribou subjects through stylization. The animal’s forms are simplified here, attenuated there, exaggerated here and there, to create the artist’s vision of the perfect caribou.” The idea of Osuitok’s idealized “vision” of the animal cannot be stressed enough, for it lies at the heart of what makes his finest versions such sublime works of art.

Osuitok’s caribou really are idealizations rather than portraits. We think this is because he was pushing himself to the limits as an artist rather than an observer. We can almost imagine Osuitok asking himself: How thin can I carve those legs before they break? How much can I refine the shape of the neck and head before they become abstract shapes?

The stance of Standing Caribou shows it with its head is raised high, which suggests that the animal has stopped walking and is scenting danger in the air. Here Osuitok has created an exquisitely crafted masterpiece, beautifully poised and supremely elegant in every aspect of its sculptural form. In short: a vision.

Lot 34

OSUITOK IPEELEE, R.C.A. (1923-2005), KINNGAIT (CAPE DORSET)

Mother and Child, Scraping a Skin, c. 1980-82

ESTIMATE: $40,000 — $60,000

In Jean Blodgett’s article on Osuitok she notes: “Representations of men… are far outnumbered by those of women. His representations of the female range from portrait busts with delicate facial features, long eyelashes, pert noses, and elaborate braids, to the buxom figures of his fisherwomen. He pays tribute to the Inuit woman’s ability to fish, sew and care for children, and he frankly admires their physical form.” [1]

This impressive and exceptionally lovely Mother and Child, Scraping a Skin reminds us of the slightly smaller but equally fine Kneeling Woman Scraping a Skin offered in the First Arts July 2020 sale (Lot 80). The composition here is rather more complex, however; the mother carries a toddler in her amautiq, and the sculpture draws more attention to the woman’s work, as she scrapes a sealskin draped over a large stone. But what we are really drawn to are the gorgeous faces of the subjects. It is obvious that the woman’s thoughts are elsewhere; in fact, both she and her child wear contemplative, even serious expressions. Certainly, the woman seems to have paused in her work. Brilliantly, Osuitok has created a work of art that delivers not only a wonderful sense of timelessness but also two fine portraits of pensiveness and intelligence in his subjects. Haunting and remarkable.

1. Jean Blodgett, “Osuitok Ipeelee” in Alma Houston, ed., Inuit Art: An Anthology, pp. 45-46. A lovely standing Fisherwoman from 1963 is illustrated in this article.

Lot 61

OSUITOK IPEELEE, R.C.A. (1923-2005), KINNGAIT (CAPE DORSET)

Shaman, mid 1970s

ESTIMATE: $18,000 — $28,000

Published: Jean Blodgett, “Osuitok Ipeelee” in Alma Houston ed., Inuit Art: An Anthology, (Winnipeg: Watson and Dwyer Publishing, 1988), p. 47.

One of Osuitok’s ancestors, Ohotok, was considered to have been a great shaman, and in 1970 Osuitok told Dorothy Eber that as a young man he had known many men and women who were, or had been, shamans. [1] In conversation with Jean Blodgett, Osuitok also recalled that as a young man out hunting with his father, “he saw three seals turning into humans. ‘I know it’s not just a fairy-tale story that animals can turn half-people. I’ve actually seen it happen.’” He also shared that he had heard that his own father had been seen as an animal. [2]

These comments put quite an interesting perspective on this remarkable sculpture by the artist. Blodgett’s description of Shaman (which, along with the illustration is on p. 47 of her article on Osuitok in Alma Houston’s book) is quite extensive. She mentions the shaman’s hands transforming into narwhal heads; his tusk-like teeth; the harpoon head jutting from the top of the shaman’s head; and his facial markings that resemble women’s tattoos but, according to Osuitok, are purely decorative.

The shaman’s tusk-like teeth, the harpoon head, and the “tattoos” all speak to the supernatural powers of shamans, and this shaman in particular. Carved animal teeth were often used in shamanic performances; here they echo the actual tusks of the two narwhals. The harpoon head also visually echoes the animals’ tusks – but more than this, it refers to the traditional weapon used to hunt narwhals and other marine mammals, as well as the shamanic feat of spearing oneself without injury. The facial markings, if not signs of female beauty, might then be seen as symbols of the shaman’s power of transformation.

To our eyes, Osuitok’s Shaman is not so much an image of shamanic transformation, but rather one of shamanic control. This shaman, outfitted with his tusks, harpoon, and facial markings, seems to be performing at a séance for an audience that includes us. It feels as he is summoning or conjuring up the animals; the two narwhal heads look almost like large hand puppets. The image is marvellously theatrical but also ruggedly powerful and offers us a rare glimpse into another aspect of Osuitok’s brilliant mind.

1. See Dorothy Harley Eber, “Talking with the Artists” in In The Shadow Of The Sun, 1993, p. 436.

2. Jean Blodgett, “Osuitok Ipeelee” in Alma Houston, ed., Inuit Art: An Anthology, p. 46.