STRANGE BEASTS: SURREALIST SCULPTURES BY ELI SALLUALU QINUAJUA

After complaints by carvers in Puvirnituq (Povungnituk) that their creativity was being hemmed in by the rather restrictive and tame tastes of their southern audience, the anthropologist Dr. Nelson Graburn — who was at the time on a research trip in the community, completing a study not simply about Inuit art but rather concerned with how the Inuit artists themselves perceived the practice — organized a competition that encouraged artists to create works that were takushurnaituk or “not seen before.”

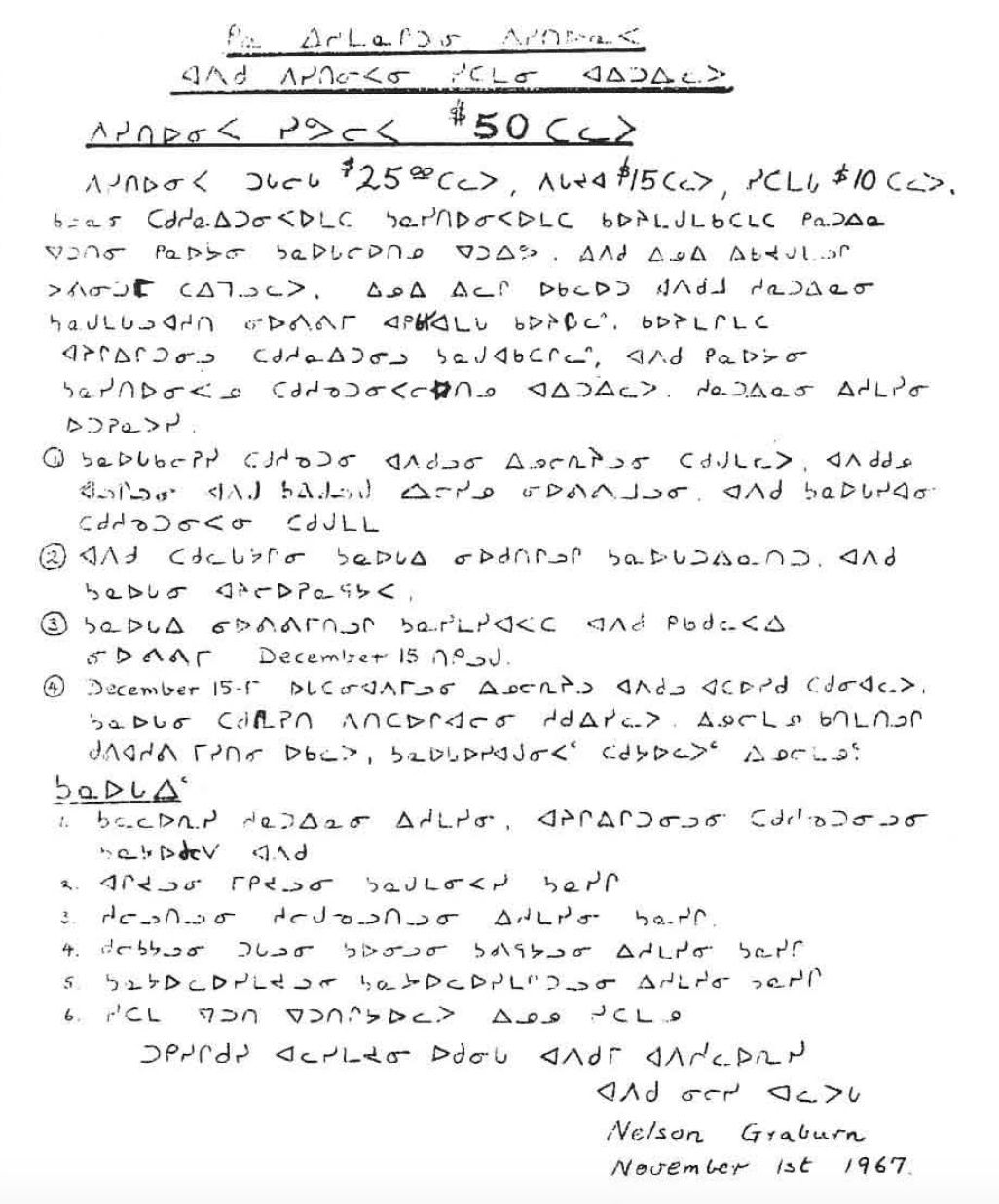

In fall of 1967, leaflets of Dr. Graburn’s handwritten call for submissions were distributed to more than 100 carvers [See Fig. 1].

Fig.1

Dr. Nelson Graburn’s call for submissions, 1 November 1967, reproduced in Diana Trafford, “Takushurnaituk: Povungnituk Art,” North/Nord magazine, March-April 1968, p. 55.

Graburn’s challenge reads, “Who is best at carving new thoughts? Apirku [Graburn]will give to the four cleverest.” Specifics for the carvings were adequately simple; anything but milquetoast. Graburn instructed:

1. Make anything that is in your thoughts. Different ones or imaginative ones Apirku orders to be made.

2. Big ones or small ones, carve the ones you want to carve most.

3. Realistic or unrealistic, whatever is in your thoughts, carve it.

4. Soapstone or ivory or bone or metal, carve whatever you want.

5. Something that you have carved before or that has never been carved before, carve whatever you want.

6. No [one] will get more than one prize.

With these radical new stipulations for creation initiated, submissions poured in. After a preliminary round of judging, a total of eleven works of the thirty-one selected were by Eli Sallualu Qinuajua. On December 21st, the final judging took place. Eli Sallualu was awarded the grand $50 prize on merit of all his technical skill and imagination, as evidenced by the wealth of outstanding works that he submitted.

In his essay “The Povungnituk Paradox: Typically Untypical Art” for the 1977 Winnipeg Art Gallery exhibition catalogue Povungnituk organized by Jean Blodgett, George Swinton describes at some length the “fantastic” branch of sulijuk realism prevalent in Puvirnituq art,

The third paradox of this “truth-seeking” is the fantastic alternative: gargoyle-like abstractions with mysterious eyes set in grotesque monster shapes, anticipated by Bosch and Goya, but conceived by Eli Sallualuk, Levi Smith, Isa Sivuarapik and others as accurate representations of dreams, fears, and well-known spirit configurations, The exact shapes, with their precise definition of details never seen but clearly envisaged, remind us of the old and world-wide traditions of picturing the fantastic and grotesque with utmost clarity, faithfulness and undeniable authority and exactness - the fantastic turned into superclear reality, the unreal into real, imagination into fact, the invisible into truth, reality, sulijuk (p. 23).

In her article “Surrealism and Sulijuq: Fantastic Carvings of Povungnituk and European Surrealism” (Inuit Art Quarterly, Winter 1994:4-10), Amy Adams describes the “uncanny” resemblance between Sallualu’s sculptures and figures in the paintings of European artists as diverse as Hieronymus Bosch and Salvador Dali. The contorted postures, fleshiness, knobby limbs, teeth, tendrils and other attributes give Sallualuk’s work a true “surrealist” quality. The sculptures can exude sexuality, horror, and grisly humour in larger or smaller doses, and yet they are delightful and intriguing and even beguiling in their appearance, not to mention beautifully executed. Sallualu deserves his status as one of Inuit art’s most imaginative and determined talents.

Eli Sallualu Qinuajua’s sculptures can be found in the collections of the National Gallery of Canada, the Winnipeg Art Gallery, the Art Gallery of Ontario, the Canadian Museum of History, the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, the Musee de la civilisation in Quebec City, the UBC Museum of Anthropology and other public collections. Sallualu’s work has been included in dozens of public exhibitions and one solo exhibition in 1985.

Literature: For published examples of Eli Sallualu Qinuajua’s work, see the WAG catalogue and Amy Adams article. See also Gerald McMaster ed., Inuit Modern (AGO, 2010); Ingo Hessel, Inuit Art (1998); Darlene Wight, Creation and Transformation (WAG, 2012); George Swinton, Sculpture of the Inuit (M&S, 1972/92); Darlene Wight, The Harry Winrob Collection (WAG, 2008); and numerous other publications.

The effect of the 1967 competition on Sallualu was a lasting one. For the remainder of his artistic career, this artist of independent spirit gave free reign to his fervent imagination with great ardour, creating works that can be categorized as monstrous, grotesque, bizarre, and, above all, fantastic, in every sense of the word. While some of his colleagues pursued the style for a time or periodically, Sallualu made it his life’s work. Seemingly overshadowed by the similarly obsessed — such as Joe Talirunili and Davidialuk Alasua Amittu whose styles could be described as more in the “folk art” vein, and also by fellow artists whose styles encompassed the more typical descriptive naturalism of camp and hunting scenes — Sallualu remained true to his vision to the end.

Works may be viewed by appointment only at A.H Wilkens Auctions & Appraisals. To obtain condition reports and additional images, please contact info@firstarts.ca or 647-286-5012.

On View;Monday 28 September 28 - Monday 2 November 2020 by appointment only |

LOCATIONA.H Wilkens Auctions & Appraisals One William Morgan Drive |

VIEW EXHIBITION

-

ELI SALLUALU QINUAJUA (1937-2004) PUVIRNITUQ (POVUNGNITUK)Fantastic Creature, 1978stone, 6.75 x 5.5 x 17 in (17.1 x 14 x 43.2 cm)

ELI SALLUALU QINUAJUA (1937-2004) PUVIRNITUQ (POVUNGNITUK)Fantastic Creature, 1978stone, 6.75 x 5.5 x 17 in (17.1 x 14 x 43.2 cm)

dated and signed "78 / ELI". -

ELI SALLUALU QINUAJUA (1937-2004) PUVIRNITUQ (POVUNGNITUK)Curious Creaturestone, 2 x 3 x 1.75 in (5.1 x 7.6 x 4.4 cm)

ELI SALLUALU QINUAJUA (1937-2004) PUVIRNITUQ (POVUNGNITUK)Curious Creaturestone, 2 x 3 x 1.75 in (5.1 x 7.6 x 4.4 cm)

signed, "ᐃᓚᐃ". -

ELI SALLUALU QINUAJUA (1937-2004) PUVIRNITUQ (POVUNGNITUK)Creature with Tendrils, c. 1970stone, 5.5 x 2.25 x 2 in (14 x 5.7 x 5.1 cm)

ELI SALLUALU QINUAJUA (1937-2004) PUVIRNITUQ (POVUNGNITUK)Creature with Tendrils, c. 1970stone, 5.5 x 2.25 x 2 in (14 x 5.7 x 5.1 cm)

signed "ELI". -

ELI SALLUALU QINUAJUA (1937-2004) PUVIRNITUQ (POVUNGNITUK)Watchful Creaturestone, 2.5 x 2.5 x 1.5 in (6.3 x 6.3 x 3.8 cm)

ELI SALLUALU QINUAJUA (1937-2004) PUVIRNITUQ (POVUNGNITUK)Watchful Creaturestone, 2.5 x 2.5 x 1.5 in (6.3 x 6.3 x 3.8 cm)

unsigned. -

ELI SALLUALU QINUAJUA (1937-2004) PUVIRNITUQ (POVUNGNITUK)Clawed Creature with Two Great Eyesstone, 2.75 x 5.5 x 2.75 in (7 x 14 x 7 cm)

ELI SALLUALU QINUAJUA (1937-2004) PUVIRNITUQ (POVUNGNITUK)Clawed Creature with Two Great Eyesstone, 2.75 x 5.5 x 2.75 in (7 x 14 x 7 cm)

signed, "ᐃᓚᐃ". -

ELI SALLUALU QINUAJUA (1937-2004) PUVIRNITUQ (POVUNGNITUK)Skulking Creaturestone, 1.75 x 3.5 x 1.75 in (4.4 x 8.9 x 4.4 cm)

ELI SALLUALU QINUAJUA (1937-2004) PUVIRNITUQ (POVUNGNITUK)Skulking Creaturestone, 1.75 x 3.5 x 1.75 in (4.4 x 8.9 x 4.4 cm)

unsigned. -

ELI SALLUALU QINUAJUA (1937-2004) PUVIRNITUQ (POVUNGNITUK)Grimacing Creaturestone, 4.75 x 5 x 1 in (12.1 x 12.7 x 2.5 cm)

ELI SALLUALU QINUAJUA (1937-2004) PUVIRNITUQ (POVUNGNITUK)Grimacing Creaturestone, 4.75 x 5 x 1 in (12.1 x 12.7 x 2.5 cm)

signed, "ᐃᓚᐃ". -

ELI SALLUALU QINUAJUA (1937-2004) PUVIRNITUQ (POVUNGNITUK)Prowling Creaturestone, 4.25 x 4.75 x 2 in (10.8 x 12.1 x 5.1 cm)

ELI SALLUALU QINUAJUA (1937-2004) PUVIRNITUQ (POVUNGNITUK)Prowling Creaturestone, 4.25 x 4.75 x 2 in (10.8 x 12.1 x 5.1 cm)

unsigned. -

ELI SALLUALU QINUAJUA (1937-2004) PUVIRNITUQ (POVUNGNITUK)Fish Creaturestone, 2.5 x 5 x 3 in (6.3 x 12.7 x 7.6 cm)

ELI SALLUALU QINUAJUA (1937-2004) PUVIRNITUQ (POVUNGNITUK)Fish Creaturestone, 2.5 x 5 x 3 in (6.3 x 12.7 x 7.6 cm)

signed, "ELI". -

ELI SALLUALU QINUAJUA (1937-2004) PUVIRNITUQ (POVUNGNITUK)Two Fantastic Creaturesstone, 4.25 x 6.75 x 2 in (10.8 x 17.1 x 5.1 cm)

ELI SALLUALU QINUAJUA (1937-2004) PUVIRNITUQ (POVUNGNITUK)Two Fantastic Creaturesstone, 4.25 x 6.75 x 2 in (10.8 x 17.1 x 5.1 cm)

signed, "ELI". -

ELI SALLUALU QINUAJUA (1937-2004) PUVIRNITUQ (POVUNGNITUK)Clawed Creature with Tendrilsstone, 2.75 x 4 x 2 in (7 x 10.2 x 5.1 cm)

ELI SALLUALU QINUAJUA (1937-2004) PUVIRNITUQ (POVUNGNITUK)Clawed Creature with Tendrilsstone, 2.75 x 4 x 2 in (7 x 10.2 x 5.1 cm)

signed, "ELI". -

ELI SALLUALU QINUAJUA (1937-2004) PUVIRNITUQ (POVUNGNITUK)Creaturestone, 4.75 x 7 x 2.75 in (12.1 x 17.8 x 7 cm)

ELI SALLUALU QINUAJUA (1937-2004) PUVIRNITUQ (POVUNGNITUK)Creaturestone, 4.75 x 7 x 2.75 in (12.1 x 17.8 x 7 cm)

signed, "ELI".